Richard Saunders, President of the Australian Skeptics Inc., sent us this report on a "psychic" who has borrowed part of my name without permission:

Richard Lead and I from the Australian Skeptics went to see the stage show of "The Amazing Valda." We sat in the audience of about 500 and wondered what she might have up her sleeve. We're always on the lookout for a new trick or angle, and who knows? We may even discover a real psychic.Valda began her act by telling us that we should all buy her books. Then we were informed that a "young lady" would be dancing on stage throughout her act. We looked — no one else came on stage. Ah! It was a spirit dancing on stage! Valda told us that only clairvoyants could see her. Sure enough, a few hands went up. Over the next hour, this invisible dancer would bump and prod Valda without warning. How rude!

Here are a few, I hesitate to say, "highlights" from her act, and yes, "messages from loved ones" means talking to the dead. Valda tried to get a hit by using the initial "D" with a man in his late fifties. She kept at it until it was apparent that the man knew of no one that fit. OK, how to get out of this? Ah! "D" stands for "Dad." The initial "H," to a lady also in her late fifties, met with a blank. Who is "H"?" Finally Valda said that "H" stands for "Helper"! "They're telling me that you're a Helper!"

What is it about ghosts and letters of the alphabet?

Another lady was asked, "Who liked to cook....scones? She's on the other side?" Again, not a hit. "Cooking scones" quickly turned into "eating scones," which turned into "reading books," which turned into "reading books about scones," which turned into "eating scones while reading books," and so on.

"Who was it who liked gardening? Is it you? Was it someone else? Was it anybody?"

Although Valda's promotions say she "will answer questions from the audience," it was in fact Valda who asked all the questions. And asked, and asked, and asked. "Who is....? Who does.....? Who is the initial.....? Is she on the other side? Can you relate to this? What was.....? Is it you, or the person next to you?"

It seems Valda picked up her "cold reading" technique in dribs and drabs rather than making any attempt to study the art, and it really showed in the low standard of her routine. It was a clumsy mixture of meaningless New Age doubletalk, channeling, and appeals to "universal love." I wish I could say the rest of her act was better, but she continued to flounder from person to person, spirit to spirit, rarely getting a "hit," and at times I almost felt sorry for her.

But then came a new low. The 20th of October, the day we saw her show, was designated as a "National Day of Mourning" for the victims of the Bali bombing here in Australia. Earlier in the day, we had all stood for a minute's silence. At that time I told Richard that if Valda tried to contact the dead from this recent tragedy, I would need to be restrained in my seat. When the moment came, I was too sickened to move.

We got to do this because the sprits just said, "Join hands," as the people who have "gone over" from Bali have been trotting around here. They just said "It's a sea of love," and your love is getting them to be accepted on the other side, with those from the American tragedy.Valda ended her act by telling us that we should all buy her books.

I'm afraid The Amazing Valda is simply the worst cold reader I have ever seen. I could only recommend she buys and studies "Full Facts Book of Cold Reading" by Ian Rowland. She is also to be strongly condemned for twisting a day of mourning for a national tragedy into her act. The insult to the dead and grieving of Bali (and the US) was nothing short of appalling, and in the worst possible taste. Do I think Valda really believed in what she was saying? I doubt it, but I cannot be sure. If she did, she's in need of professional help.

What did I learn? The only new trick I picked up from Valda was the way she trained the audience to applaud after each "reading," no matter how pathetic it was. We were "clapping to encourage the spirits," she said. The result was to have the hall full of applause every four minutes or so. Very clever, Valda, though some professional magicians of my acquaintance manage this trick with much more aplomb and good humor. I also learned that someone who is rotten at cold reading can easily get away with it.

Cold reading is an art anyone can learn, and the people who perform cold reading are rightfully thought of as artists. As with any performance art, there are good performers, great performers and then there are those who should just give up and find another outlet for their creativity. Valda, it's time to move on. You are an embarrassment to the art.

Okay, but this just proves again that skill is not required when the audience needs these things to be true. Valda, despite her lack of talent, has her own radio call-in show in Australia, plus a newspaper column. She doesn't have to be good, just free of ethics and of respect for her victims.

You'll recall that we mentioned here the BioMagnetics' website, which proudly announces an endorsement of their flummery by Australian Kevin Dalton, who they say was "awarded the Australian Sports Medal by Queen Elizabeth II for his use of the Davis and Rawls magnetics with sports participants, including Australian Olympic winners." We wondered about the prestige of that award, given in the category "Miscellaneous" (?) to Mr. Dalton, then reader Tara Ogawa informed us that the "Australian Sports Medal" may not be quite as impressive as it sounds. Says Tara:

Over 18,000 "Australian Sports Medals" were progressively distributed and presented during the year 2000. If you consider that Australia only has a population of about 19 million, that means that during the year 2000, about one in a thousand people received one...My incredible psychic powers tell me that Queen Elizabeth had very little to do with the presentation of Mr. Dalton's medal. The Governor-General presents high Australian honors; lower honors are presented by minor officials. The Australian Sports Medal might have been presented by Mr. Dalton's boss or local member.

Thank you for that analysis, Tara. I'll add my observation that according to those figures, that medal was awarded to some 50 persons a day, too! Just think of the postage!

Reader Germán Buela writes that the British musician Mike Oldfield has set up a web site with what he calls, a "telepathy game." It's at http://www.mikeoldfield.com/poll.htm . Players are asked to look at four shapes and guess which shape Mike chose. The page says, "... usually the first answer that comes into your mind is correct, so trust yourself." Germán opines:

It's little things like these that help propagate magical thinking: people might think that this game, lacking proper controls, serves as a scientific test for telepathy. At first sight I see a problem. The first shape that "comes into my mind" is effectively the one that most people have voted (once you make your choice, you can see how many people have chosen each shape), and I had suspected that right away. This is not due to telepathy but to the shape itself and its location: you are led to pick that one. There is an important factor in the cost of an advertisement in magazines, apart from size: its location, and I don't mean the obvious places like back cover, centerfold, etc., but because we tend to end up looking at a certain spot on an opened page. I think the same thing worked here, and I wouldn't be at all surprised that it worked on Mike as well, which might seem like a confirmation of telepathy when his choice is revealed in January.I am not being explicit on which that location is, and why the shape catches your eye. But I'm sure critical thinkers will arrive at the same conclusion. I have also commented on this on my website (in Spanish): http://www.asalup.org/lacolumna

Putting in my own expertise here, I'll tell you that by far the most-chosen of the five standard ESP-cards symbols (circle, plus-sign, wavy lines, square, and five-pointed star) is the star. Since this "game" involves only four symbols, and one is star-like, I'll bet on that one to be the winner. Yes, Germán, this is a really poor "game," and a worse "test."

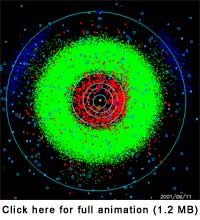

Jim McGaha, personal friend, prominent amateur astronomer and deep-sky photographer, sent me this quotation from a paper that is well-known to "New Age" astrologers, "The Significance of Asteroids," by Jacob Schwartz:

Jim McGaha, personal friend, prominent amateur astronomer and deep-sky photographer, sent me this quotation from a paper that is well-known to "New Age" astrologers, "The Significance of Asteroids," by Jacob Schwartz:

So few astronomers understand astrology or the archetypal power of names. Is their seeming arbitrary naming the factor in creating the vibration? Or is the vibration already there, waiting to be acknowledged, and so strong that the asteroid itself dictates its name to the astronomer via the circuitry of the unconscious mind that links one to the holographic mysteries of the universe?

I consider all that doubtful. How could asteroid #3163 (1981QM) have been named "Randi"? What possible set of vibrations would bring that about....?

Reader Steve Vaughn writes:

Reading your latest column on your site I was reminded of a man in my Navy Reserves unit in San Jose, California in the mid 80's. This gentleman, a Sea Bee, claimed that he could dowse for gold! Not only that, but if someone brought in a river map he could dowse the map and mark down where gold could be located and all he asked for was 10% of what was found.Since virtually every inch of creek and river in California is claimed by a gold hunter group, one has to join this group and then you can have access to the rivers and creeks. This costs about $1500 plus yearly fees. So this guy would have members of the gold hunters show up and he would have his lil' dowsing rod (about 6 inches long) and he would go over the map, it would twitch around, he'd mark spots, and then wait for his percentage. I called him on this because even with my basic knowledge of how water moves, one can pretty much see on the map where gold would likely be deposited. My challenge of having me find the likely spots on the same map and he doing his dowsing and comparing notes, was turned down.

I've not seen those guys in years but I wonder how many people contractually agreed to pay this fraud out of the little gold that they would find with our without his help.

Steve, this is the old racing-tout game played with gold.... In effect, the guy can't lose, because those who are unsuccessful don't get back to him, and those who are winners — sometimes — will pay off. Yet another swindle I didn't think of....

A man who had seen me on Chinese TV, sent in a list of various ailments he thought I had, a list which was very wrong. As usual, he ascribed to me the problems that a 74-year-old man often has, but that I don't. In response to his application for the JREF million-dollar prize, which was sent in by his daughter, and which said that her father could diagnose a person just by seeing their photo, I replied as I usually do to such a claim. This claim is very, very, common here at the JREF.

I sent him ten photos of persons I know, simply asking him to tell me whether each person shown was dead or alive, rather than having to go through evaluating the long, convoluted, vague, descriptions such as, "Feels tired and weak at night, liver unbalance and bile excess, tingling in ears" that are part of the usual diagnosis. The simplified test has never been accepted by any of these "diagnosticians," who usually just stop corresponding at that point. But this man offered reasons for not doing such a basic test. Headed, "Qigong is not a divination or necromancy," the reply came, written by his daughter:

Dear Mr. Randi,Thank you for your prompt reply.

Firstly, Qigong is not the panacea, it can solve some problems, but not all of the human diseases, it is a very ancient physical theory in China, it is based on the Chinese Medicine, according to the flow of blood, venation structure. In the science age, Qigong could not heal all the disease.

Qigong, means someone have more energy than the ordinary person, but not really a superman, in a short word, he owns talent or performance in a special condition.

As to the photos, my father could not tell you who is alive or dead, sorry for that. One reason is his or her soul is still existent, but my father could give the diagnosis for him or her. I must to say, it will allow a little discrepancy.

Qigong is not a divination or necromancy, it is inductive for magnetic field between the acceptor and dispenser, if you read some Chinese Wushu [Chinese martial arts] novels before, you could understand more easily.

I responded:

I believe that if your father can diagnose illnesses, as he claims he can, he should be able to diagnose death rather positively. This is the easiest, most direct, test for claims of diagnosis. You have refused it, and that is your decision.

Please recognize this procedure for what it is. We use it in order to avoid getting involved with very complicated exchanges and arguments. It's like summarily eliminating race-cars that have no tires, rather than having to examine them for safety attachments and conformity with track rules. Even I, with no medical training, can detect the symptom known as "death." If this man, who says he can diagnose complicated defects such as blocked arteries and tumors, cannot diagnose death, his technique needs work. We've offered other similar applicants the opportunity of determining which of a selection of persons might have an artificial leg, and they've always told us that "spiritually" the original leg is still there, and still gives out "vibrations" to them. They are experienced at handling problems like this, and they know that their followers are happy to accept their reasoning.

It is likely that we will not hear back from this applicant. This is the choice that most of these folks take when faced with a simple, direct, uncomplicated test. When we're asked why we don't issue a list of applicants for the prize, we cite this as one of the reasons. Did this applicant actually apply? Well, almost. Do you begin to see the problem?

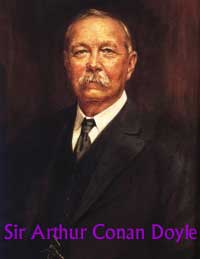

Back in 1922, a remarkable book, "The Coming of the Fairies," by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, was published in the U.K. I say "remarkable," because it seemed not possible that Sir Arthur actually meant it to be taken seriously — but he did. It dealt with the photos taken by cousins Elsie Wright and Frances Griffiths, five years earlier, which they claimed were of fairies and other supernatural creatures they had encountered in Cottingley Glen, near their home in Bradford, Yorkshire.

[Aside: at the JREF, we have the original first edition of the Conan Doyle book that was presented, with inscription, to Elsie Wright, by the author.]

The photos were blatantly amateurish fakes, even for the state of photography as it was at that time. The matter is discussed in detail elsewhere on these pages. Just do a "search" for "Cottingley."

The photos were blatantly amateurish fakes, even for the state of photography as it was at that time. The matter is discussed in detail elsewhere on these pages. Just do a "search" for "Cottingley."

A distinguished writer of the day, Maurice Hewlett (1861-1923), raised some objections to the fairy photos, which were then known as the Carpenter photos because Conan Doyle had concealed the girls' real identities. Hewlett's objections were in some ways well-founded, in others, not. Certainly they were far better than the responses to them offered by theosophist Edward L. Gardner, Conan Doyle's "researcher" and spokesman. I'm interested in the fact that neither side in this argument seemed adequately competent. Taken from the 1922 Conan Doyle book, Mr. Hewlett's contentions were as follows:

The stage which Sir A. Conan Doyle has reached at present is one of belief in the genuineness of what one may call the Carpenter photographs, which showed the other day to the readers of the Strand Magazine two ordinary girls in familiar intercourse with winged beings, as near as I can judge, about eighteen inches high.

Randi comments: First bad guess. Unless the girls had very big heads, those fairies were no more than 10 to 11 inches in height. A poor start to a critique.

If he [Conan Doyle] believes in the photographs, two inferences can be made, so to speak, to stand up: one, that he must believe also in the existence of the beings; two, that a mechanical operation, where human agency has done nothing but prepare a plate, focus an object, press a button, and print a picture, has rendered visible something which is not otherwise visible to the common naked eye.

Hewlett could not have known about infra-red photography, which only developed in the 1920s, but his second point is certainly not valid. And, fairies were said to be visible to innocent little girls, and both girls had claimed they actually saw them. His first point is obviously true, yet rather pointless; Sir Arthur believed in almost everything, so fairies were not a leap of faith for him.

That is really all Sir Arthur has to tell us. He believes the photographs to be genuine. The rest follows. But why does he believe it? Because the young ladies tell him that they are genuine. Alas!

Here, Hewlett is very probably right. Conan Doyle simply could not bring himself to accept that little girls would lie, particularly to him. He was a perfect foil for their game.

Sir Arthur cannot, he tells us, go into Yorkshire himself to cross-examine the young ladies, even if he wishes to cross-examine them, which does not appear. However, he sends in his place a friend, Mr. E. L. Gardner, also of hospitable mind, with settled opinions upon theosophy and kindred subjects, but deficient, it would seem, in logical faculty. Mr. Gardner has had himself photographed in the place where the young ladies photographed each other, or thereabouts. No winged beings circled about him, and one wonders why Mr. Gardner (a) was photographed, (b) reproduced the photograph in the Strand Magazine.

Gardner certainly was not very bright, and hopelessly crippled by his devout belief in Theosophy — a religion which preached, and still preaches, the literal reality of fairies. In addition, he was the agent of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, a paramount figure of that time, and pleasing the boss has always been a high priority with some people. However, I have no difficulty understanding why Gardner would want his photograph to appear in one of England's leading popular magazines....! Hewlett refers in what follows, to a current news item of the day:

The only answer I can find is suggested to me by the appearance of the Virgin and Child to certain shepherds in a peach-orchard at Verona. The shepherds told their parish priest that the Virgin Mary had indeed appeared to them on a moonlit night, had accepted a bowl of milk from them, had then picked a peach from one of the trees and eaten it. The priest visited the spot in their company, and in due course picked up a peach-stone. That settled it. Obviously the Madonna had been really there, for here was the peach-stone to prove it.I am driven to the conclusion that Mr. Gardner had himself photographed on a particular spot in order to prove the genuineness of former photographs taken there. The argument would run: The photographs were taken on a certain spot; but I have been myself photographed on that spot; therefore the photographs were genuine. There is a fallacy lurking, but it is a hospitable fallacy; and luckily it doesn't very much matter.

I don't find that a fair objection, at all. Gardner was quite properly showing readers the location where the girls' photographs had been taken, and providing an idea of scale by simply being in the photograph. Hewlett is not on firm ground here. He continues:

The line to take about a question of the sort is undoubtedly that of least resistance. Which is the harder of belief, the faking of a photograph or the objective existence of winged beings eighteen inches high? Undoubtedly, to a plain man, the latter; but assume the former. If such beings exist, if they are occasionally visible, and if a camera is capable of revealing to all the world what is hidden from most people in it, we are not yet able to say that the Carpenter photographs are photographs of such beings. For we, observe, have not seen such beings. True: but we have all seen photographs of beings in rapid motion — horses racing, greyhounds coursing a hare, men running over a field, and so on. We have seen pictures of these things, and we have seen photographs of them; and the odd thing is that never, never by any chance does the photograph of a running object in the least resemble a picture of it.

I find this difficult to understand, let alone accept. Hewlett was out of his depth here. Or perhaps he'd not seen many photographs. In any case, he missed far more obvious aspects that clearly damn the photos as fakes. See my references elsewhere in these pages.

The horse, dog, or man, in fact, in the photograph does not look to be in motion at all. And rightly so, because in the instant of being photographed it was not in motion. So infinitely rapid is the action of light on the plate that it is possible to isolate a fraction of time in a rapid flight and to record it. Directly you combine a series of photographs in sequence, and set them moving, you have a semblance of motion exactly like that which you have in a picture.

Nonsense. Everything depends on the speed of the camera's shutter, and whether or not the aperture and the sensitivity of the film is enough to register the figure adequately.

Now, the beings circling round a girl's head and shoulders in the Carpenter photograph are in picture flight, and not in photographic flight. That is certain. They are in the approved pictorial, or plastic, convention of dancing. They are not well rendered by any means. They are stiff compared with, let us say, the whirling gnomes on the outside wrapper of Punch [a popular humor magazine of the day, still published]. They have very little of the wild, irresponsible vagary of a butterfly. But they are an attempt to render an aerial dance — pretty enough in a small way. The photographs are too small to enable me to decide whether they are painted on cardboard or modelled in the round; but the figures are not moving.

One other point, which may be called a small one — but in a matter of the sort no point is a small one. I regard it as a certainty, as the other plainly is. If the dancing figures had been dancing beings, really there, the child in the photograph would have been looking at them, not at the camera. I know children.

And knowing children, and knowing that Sir Arthur Conan Doyle has legs, I decide that the Miss Carpenters have pulled one of them. Meantime I suggest to him that epochs are born, not made.

I'll allow my readers to refer to the comments I've already published, both in my book, "Flim-Flam!" and on previous pages of this site, to see just how lame this criticism is. But what follows in an attempt at rebuttal by E.L. Gardner, is even worse.

I could have wished that Mr. Hewlett's somewhat playful criticism of the genuineness of the photographs of fairies appearing in the Strand Magazine Christmas number had been more clearly defined. The only serious point raised is the difference between photographic and pictorial representation of motion — Mr. Hewlett maintaining that the latter is in evidence in the photographs.With regard to the separate photographs of the sites, surely the reason for their inclusion is obvious. Photographic experts had stated that though the two negatives revealed no trace of any faking process (such as double exposure, painted figures on enlargements rephotographed, set-up models in card or other material), still it could not be held to be impossible to obtain the same class of result by very clever studio work.

No, Mr. Gardner, "very clever studio work" — as we now know — was not at all needed. There was no double exposure (except for an accidental one, as I pointed out previously) but there certainly could not have ever been any authoritative statement by any "expert" that "set-up models" were not used. How could that have possibly been established?

Also, certain points that needed elucidation were the haze above and at the side of the child's head, and the blurred appearance of the waterfall as compared with the clarity of the figures, etc. An inspection of the spots and photographs of their surroundings was surely the only way to clear up some of these. As a matter of fact, the waterfall proved to be about twenty feet behind the child, and hence out of focus, and some large rocks at the same distance in the rear, at the side of the fall, were found to be the cause of the haziness. The separate photographs, of which only one is published of each place, confirm entirely the genuineness of the sites — not the genuineness of the fairies.

This incredible statement by Gardner surely demonstrates his ignorance. That "haziness" is due to the fact that when this negative was printed, the darkroom technician used the only method available at the time, to bring out the face of the girl Frances. It's called, "dodging." Since Frances was rather in the dark, behind the figures, a regular "flat" printing of the negative which would have shown the figures and the waterfall appropriately, would have rendered the girl's face very darkly. In order to bring it out lighter, while the printing paper was being exposed to the light, the technician would have used a finger or a tool to shield that portion of the paper. That's an inexact procedure, and often makes an indistinct "halo" effect — which is exactly what is shown here. I have seen many different prints of this photos, and it's evident that they were all "dodged" in the printing process.

The "rocks" had nothing to do with the haziness, as Gardner claimed. He continued:

In commenting on the photography of a moving object, Mr. Hewlett makes the astonishing statement that at the instant of being photographed it is not in motion (Mr. H.'s italics). I wonder when it is, and what would happen if a camera was exposed then! Of course the moving object is in motion during exposure, no matter whether the time be a fiftieth or a millionth part of a second, though Mr. Hewlett is by no means the only one to fall into this error. And each of the fairy figures in the negative discloses signs of movement. This was one of the first points determined.

Gardner is quite correct here, until he gets to the part where he says that there is movement to be seen in the figures. There is not. The fairies are sharp and clear. Those flapping wings, supposedly keeping the fairies suspended, would have been moving so fast, that even at 1/50th of a second shutter time, there would have been blurring. And very little research was needed to determine that the camera (a "Midg" box-camera) had a fastest speed of just 1/10th of a second. That's why the waterfall, moving quickly, is blurred more than distance alone would call for, and the folks at Kodak, in the UK, estimated for me that the exposure was more like two seconds, given the subdued light. Gardner continued:

I admit at once, of course, that this does not meet the criticism that the fairies display much more grace in action than is to be found in the ordinary snapshot of a moving horse or man. But if we are here dealing with fairies whose bodies must be presumed to be of a purely ethereal and plastic nature, and not with skeleton-framed mammals at all, is it such a very illogical mind that accepts the exquisite grace therein found as a natural quality that is never absent? In view of the overwhelming evidence of genuineness now in hand this seems to be the truth.

Words fail me to comment on that vapidity.......

With regard to the last query raised — the child looking at the camera instead of at the fairies — Alice [Frances] was entirely unsophisticated respecting the proper photographic attitude. For her, cameras were much more novel than fairies, and never before had she seen one used so close to her. Strange to us as it may seem, at the moment it interested her the most. Apropos, would a faker, clever enough to produce such a photograph, commit the elementary blunder of not posing his subject?

Gardner was well aware that the two girls regularly used the camera as a plaything, Elsie's father being an amateur photographer who developed and printed at his home. There was very little novelty in the situation to Frances. We now know that there were many, many, failures of the girls' efforts at trick photography, and Gardner himself had a mass of negative plates from which he prepared lantern-slides for his Theosophy talk on the Cottingley fairies. We have, at the JREF, the original box of slides that he used, and though several obvious and damning errors show up in those photos, Gardner was blind to them, due to his need to believe.

Here ends Gardner's contribution. Conan Doyle takes up the discussion:

Among other interesting and weighty opinions, which were in general agreement with our contentions, was one by Mr. H. A. Staddon of Goodmayes, a gentleman who had made a particular hobby of fakes in photography. His report is too long and too technical for inclusion, but, under the various headings of composition, dress, development, density, lighting, poise, texture, plate, atmosphere, focus, halation, he goes very completely into the evidence, coming to the final conclusion that when tried by all these tests the chances are not less than 80 per cent in favour of authenticity.

Conan Doyle's readers were not told that the Kodak lab in London had also been consulted on this matter, and declined to give an opinion. Bearing in mind the traditional politeness embraced by the British at this period of history, one must ask why this most prestigious set of experts would have chosen not to comment. Other "experts" perhaps did, though we cannot know how many were consulted before a positive opinion was obtained by Gardner.

It may be added that in the course of exhibiting these photographs (in the interests of the Theosophical bodies with which Mr. Gardner is connected), it has sometimes occurred that the plates have been enormously magnified upon the screen. In one instance, at Wakefield, the powerful lantern used threw an exceptionally large picture on a huge sheet. The operator, a very intelligent man who had taken a skeptical attitude, was entirely converted to the truth of the photographs, for, as he pointed out, such an enlargement would show the least trace of a scissors irregularity or of any artificial detail, and would make it absurd to suppose that a dummy figure could remain undetected. The lines were always beautifully fine and unbroken.

Well, we now know, from the fakers themselves, that scissors were used, that these were cut-outs, and that the experts accepted by Conan Doyle were either wrong, or knew better but were trying to gain the favor of Sir Arthur.

I prefer to believe the former of these two possibilities.

We've just passed 180 registrants for The Amaz!ng Meeting, and to our delight, Professor John C. Brown, Regius Professor of Astronomy at Glasgow, who presents "Magic of the Cosmos," a lecture series using conjuring stunts, will be attending. John is also the Astronomer Royal of Scotland, and we're very honored to have him joining us to present a paper — "Astronomy, the Ultimate Magic Show" — at the Sunday session. We seem to be rather heavy on astronomers, which pleases me no end!

We've just passed 180 registrants for The Amaz!ng Meeting, and to our delight, Professor John C. Brown, Regius Professor of Astronomy at Glasgow, who presents "Magic of the Cosmos," a lecture series using conjuring stunts, will be attending. John is also the Astronomer Royal of Scotland, and we're very honored to have him joining us to present a paper — "Astronomy, the Ultimate Magic Show" — at the Sunday session. We seem to be rather heavy on astronomers, which pleases me no end!

Had to mention this: I just bought an extended service agreement on a computer program. "Extended" hardly expresses it. Looking at the parameters of the warranty, I see that it's good for another "99,993 days." That means that in 273 years, nine months, and five days (give or take a day or so), I'll have to renew....

I'm preparing to go to Korea to tape eight TV shows that will investigate the claims of Asian "psychics" and "healers." There may be a gap in the posting of updates here, though I'm trying to get enough material submitted to last until I get back January 20th.

Happy 2003, everyone!