(Guess what? Still no response from Florsheim, nor from DKL. I wonder why?)

I've just come back from a rather harrowing series of flights

to various lecture venues, so I'm tuned to airport and airline

shortcomings. Being offered a drippy chocolate doughnut and room-temperature

coffee for breakfast on one flight, has not improved my attitude

a bit.

Airport security is a serious problem, as we all know. But my observations of how it has evolved, get me a bit worried. Until recently, operators of the system required that every computer passing through the system must be turned on and the display on the screen lit, after which it was approved. This was a silly - and dangerous - idea, since any serious would-be bomber could easily prepare a light-up screen to disguise an explosive device, knowing that was all that was necessary to get by. More recently, I've been asked to "operate" my beeper to prove that it's genuine, a ridiculous requirement under any standards. There appears to be a technically-inept person behind all this, a fact verified by the fact that now my computer bag passes through the x-ray scanner, shows nothing but a large opaque rectangle, and it passes! The examiners have no idea what might be there, but they have followed the rules, and they move right on.

Many years ago, when I lived in New Jersey, I arrived at Newark airport and found that my travel agent had erred and booked me out of JFK airport. With little time to spare, I opted to grab the next helicopter shuttle to JFK, and scooted for the gate. I placed my large suitcase on the scanner belt along with my carry-ons, passed through the frame, and stood impatiently waiting for my baggage and looking at the monitor screen. To my horror, I saw the perfect outline of a Smith and Wesson 38-caliber revolver smack in the middle of the screen. The operator was looking directly at the screen, as I was, but did not react.

(I should explain how I came to have a revolver. At that period in my career, I was performing a "mentalism" trick in which I would shoot out of a cluster of balloons, one of a specific color - while blindfolded. Wax bullets propelled by a tiny charge were enough to do the job. I will add that following this experience I switched over to a molded-plastic replica revolver that was transparent to the scanning systems.)

I hustled to the gate, expecting at any moment to hear a "Halt!" but heard nothing. Aboard the helicopter I was sure that we would be intercepted by Sidewinder ground-to-air missiles. Nothing. Upon landing at JFK I expected a SWAT team in leather and armor to place my poor body under arrest. Again, nothing. Perhaps 20 minutes after I left, the security person awoke from his trance back in Newark and exclaimed, "Revolver!" I will never know.

At one time, I traveled with several pieces of electronic equipment that were encased in the usual sheet-metal casings - all of which showed on the security screen as opaque rectangles. There was no telling what they were, or what was behind them. And that's very much the situation today, too.

No, I don't have a much better scheme to offer. That's not my field, but I think I could do a better job than is being done right now. I'm concerned about what appear to be ineffective and rather arbitrary rules that are applied to the security system at airports. Preparing dedicated transgressors by showing them how weak the system is, is not at all wise.

Andrew Harter is the one at the JREF who handles all the applications for the million-dollar prize that come in almost daily via fax, mail, and e-mail. A couple of months ago he received an application made on behalf of a lady in Lithuania who claimed remarkable diagnostic and healing powers. As usual, she had a difficult time stating exactly what these powers were and how they could be tested. Since no amount of anecdotal evidence and no number of affidavits can suffice to establish any of these claims, we asked her to go to an M.D. for validation of her claim that she had a "charge" on her hands that enabled her to heal. She sent us a note from a doctor who certified that she had a "charge" of some kind, but it said nothing more. No details were given of any test, or whether a control group had been used, or any measurements attempted. We notified this woman that we simply didn't have enough information to design a test for her claim. Much paper and many phone calls followed, but no more information was offered.

Then last Friday three women showed up at our door in Fort Lauderdale, unannounced, saying that they demanded a test be made of one of them - the claimant we'd been dealing with in Lithuania. One of the other women was simply a friend who claimed she'd been healed of cancer by the claimant, and the third was their interpreter. They were very pleasant, charming, presentable, and likable. Since they'd come such a long way, at such expense, and despite the fact that Andrew was not available at that time, I entertained the idea of allowing them to do the preliminary test. When they began giving me all the theories, philosophy, anecdotal accounts, and general information about the wonders that had been accomplished, I told them firmly that I was only interested in seeing results. The claimant asserted that she could do a diagnosis of anyone that would be 100% correct, and since I had only recently finished comprehensive medical examinations, and was due later in the afternoon to have an MRI scan, I felt that I might be the ideal subject for such a test.

I first prepared a brief videotape statement in which I outlined my general medical condition, the details about any and all difficulties that I was experiencing, and the data that was recently given to me following my medical checkups. We then invited the claimant to conduct her diagnosis. Since this was not a "double-blind" test - it couldn't be because I knew what the results should be - I remained passive and expressionless during the hand-waving procedure that ensued. Every statement that she made was tentative, and she ran down a symptom list that could be expected for a man of my age. She also added the modifier that if I did not suffer from these symptoms, I shortly would do so. She missed every one of the problems that I actually have.

I felt rather badly about all this, as I do

about any case where people are honestly self-deluded. While

I'm always comforted by the fact that they never believe any

negative evidence, and will persist in their false beliefs they

hold, I still feel that they must undergo some disillusionment

when they fail so grandly. But it was two questions that I asked

them, that provided the most information from this encounter.

You may be surprised by their answers, but it's what we have

grown to expect.

Before telling them anything about the accuracy of her statements,

I asked, "What will you say if your diagnosis is incorrect?"

"Oh, that's not possible. I'm always correct," she

said. Several times I posed this question, only to have the woman

refuse to answer simply because she could not imagine not being

correct in her diagnosis. So, I changed the question slightly.

"What sort of evidence would be sufficient to prove you

that you do not have the ability to diagnose?" I asked.

Several minutes of animated conversation among the three produced

this answer: "She is never wrong. Never!"

The claim that was being made was simply not falsifiable. They could not deal with the possibility that this woman might not have diagnostic and healing powers. No amount of evidence to the contrary of their claim would be sufficient to have them change their minds and convictions. This is not an isolated case in this respect; in examples we have dealt with, we've often found this strange attitude.

These are good people, self-deluded but innocent. The problem with all that is simply that they might be believed by persons who would count on them being genuinely able to perform as promised. This situation has the possibility of creating great tragedy, simply because of the practitioners' inability to deal with a real world. It's this kind of experience that makes our work very difficult, because the guilt lies not with the individuals concerned, but with the public misunderstanding of how things actually work.

To show my concern with proper procedure, I wrote a transcript of everything the woman had said in her diagnosis, faxed it to two of my physicians, and requested responses from them based upon their knowledge of my physical state. As this goes out on the Internet, I've not yet heard back from these gentlemen, but from what I know of my own condition, this diagnosis by the well-meaning lady from Lithuania was a resounding failure. In our opinion, she failed the preliminary test for the million-dollar prize.

Unfortunately, I'm sure that these three women will return home feeling that they've been poorly treated in respect to trying the challenge. But before they go, they will be offered the opportunity to try diagnoses of at least two other people - though I expect the results will be quite the same. We always lean over backwards in our attempts to treat people fairly.

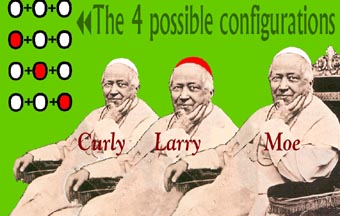

Did we get responses to the Three Caps puzzle! By far the most common was 2 red, one white, but that is not acceptable, nor is the white-white-white arrangement. This puzzle is a variation on an old theme. I've taken it and put a twist or two in, being the fiend that I am. In the illustration is a simple diagram showing the only four configurations possible.

We have to deal here with the fact that we already know that Moe's right. We have an advantage that the players don't have, and that is an important factor in working out our answers. Another thing is obvious from the start: If there are two players wearing red caps, the remaining guy knows right away what he's wearing - white. Any of these three seeing two reds, would immediately respond, and that's not what happened. The statement by a player that he does not know the answer, means that he's not looking at two red caps - which would be the only circumstance under which he could say, before any other evidence comes in, that he knows. Moe's the smartest of the three, because he sits and waits for evidence to develop.

Now

for the distribution of caps in this giddy group. It goes Curly=white,

Larry=red, and Moe=white, as shown in our illustration. You'll

also see there the four possibilities for the cap arrangements.

If both Curly and Larry had been wearing white caps, Moe would

know nothing about his own cap from that fact alone, nor from

hearing Curly's complaint, but after Larry didn't solve the question,

he would have known that he - Moe - was not wearing a red cap.

How? If Moe had been wearing red, then Larry, hearing that Curly

wasn't looking at two red caps, would have known that he himself

was wearing white, and he would have been the winner. He wasn't

the winner, as we know from our superior position. So, by elimination,

Moe knows he's wearing white. So neither white-white-white nor

white-white-red (the first two combos shown) are the configurations

we're looking for. But read on.

Now

for the distribution of caps in this giddy group. It goes Curly=white,

Larry=red, and Moe=white, as shown in our illustration. You'll

also see there the four possibilities for the cap arrangements.

If both Curly and Larry had been wearing white caps, Moe would

know nothing about his own cap from that fact alone, nor from

hearing Curly's complaint, but after Larry didn't solve the question,

he would have known that he - Moe - was not wearing a red cap.

How? If Moe had been wearing red, then Larry, hearing that Curly

wasn't looking at two red caps, would have known that he himself

was wearing white, and he would have been the winner. He wasn't

the winner, as we know from our superior position. So, by elimination,

Moe knows he's wearing white. So neither white-white-white nor

white-white-red (the first two combos shown) are the configurations

we're looking for. But read on.

Moe has to be looking at one red cap, and one white cap. If he sees Curly wearing a white cap, and Larry a red (combo #3), after Curly says that he can't figure it out, Moe has total validation that he's wearing a white cap, and he doesn't need to hear Larry's comment. Moe knows from the very first comment, that he's wearing a white cap!

But wait a minute, I hear some of you saying, "But if Moe sees Curly wearing a red cap and Larry a white one (combo #4), after Curly's comment, he'd know nothing useful in itself. But after Larry's comment, he'd know that he - Moe - is wearing a white cap!"

Gotcha! You forgot that Moe said, "I'm absolutely certain, and I knew it before the beer was on its way!" (Italics added with glee.) Moe is revealing to us that he knew right after Curly had spoken, and didn't need Larry's observation!

(Now, I got the argument that "I knew it before the beer was on its way" could also mean "I knew it before the very beginning," and I admit that I could have written, "I knew it as soon as the beer was on its way." You may have a point here, I confess. But that's why I ask for your input, so that I, too, may be educated! And do I get it? Oh, yes.

But because I've caused sleepless nights and much brain-knuckling with Curly, Larry, and Moe, I've decided to hold them over for a second week, which is only right for a successful act. But the conditions have changed. Moe, right after his victory, visited the local bar, and was struck by the beauty of the place. She hit him in the eye, - nyuk, nyuk, nyuk - and now he's wearing a blindfold, until he recovers. He can't see anything. Here's the same problem, re-stated to accommodate Moe's temporary unfortunate condition....

Curly, Larry, and Moe, having nothing much better to do one evening, agree to play a strange game. Moe, due to a temporary condition (the sordid details are not pertinent here) cannot see, and wears a blindfold. They all know that there are two red and three white caps in a drawer. They turn out the lights, each reaches into the drawer in the dark, removes one cap, and places it on his head. Then the drawer is closed, the lights are switched on, and the players sit down, each to try to guess which color of cap he himself is wearing. Fifteen minutes goes by.

These three chaps are pretty smart. Each knows that there might be ways, by observing, listening, and reasoning, of knowing what color of cap he's wearing.

Curly is the first to speak. "This is a stupid game! Whose idea was this, anyway? And whose caps are these? I don't know what color I'm wearing, and I don't care! I want a cold beer! And some of those tiny pretzels, too!" And he calls the delicatessen downstairs to order a cold six-pack and pretzels. Moe smiles, but stays silent.

Larry is next to break the silence. "I don't know what color I'm wearing, either! I agree this is a dumb game! I might have a green cap, but I'd never know it! Let's order in some pizza and play poker!" And he picks up the phone, orders pizza, and starts shuffling the cards. Moe smiles even more broadly. Then he speaks up.

"Well, I'm wearing a white cap! I'm absolutely certain, even though I can't see what colors you guys are wearing, and I knew it just before the pizza was ordered! So pass me over a cold brew! And I'll buy the pizza!"

And he's right. He is wearing a white cap. He didn't cheat. He figured it out.

Assume that all three guys are astute and clever, and that they speak the truth. Two questions: How did Moe know? And what was the distribution of caps?

(Hint: ignore the pretzels. I threw those in just to make you crazy. Nyuk, nyuk, nyuk.)

Note: we've withdrawn the note here that the Encyclopedia of Claims, Frauds, and Hoaxes of the Supernatural and Occult on-line will be coming here "soon." That was certainly our intention but we've had difficulties finding someone who has both the time and the talent to do this for us. We're still pursuing the project, but you'll no longer see the promise up there until we see it fully in view. Our apologies.

And, yes, the illustration of the square-in-a-circle-in-a-square solution said "90 degrees" rather than "45 degrees," but was correct in the text. Also, Dr. Tim Gorsky's points were numbered, 1, 2, and 4 -- rather than 1, 2, and 3. I'd had a hard week....

And -- we're getting an average of 760 "hits"

a day on this page. Great!