A grave matter of great interest has come to our attention right here in Florida. The Polk County School Board, who are in need of funds to build more classrooms, have just given final approval to an expenditure of over $560,000 for a school program to be implemented by the Starshine Foundation, a mystical New Age organization that touts "remote viewing," clairvoyance, "morphic fields," "direct knowing," "soulwork," and psychokinesis. Sue Miller Hurst, who is described as a "teacher, principal, and researcher," and who the Polk County School officials say is "now considered to be one of the world's thought leaders," is the head of Starshine. Ms. Hurst claims to be an advisor to the "MIT Center for Organizational Learning," potent credentials indeed. A phone call to MIT established that this group no longer exists, and that Ms. Hurst has not been associated with its successor, the Society for Organizational Learning, for "several years."

There are plans in Polk County to expand the budget for Starshine to $868,000. And this is a school board that desperately needs funds for legitimate learning and teaching purposes. Glowing endorsements of Hurst's claims have been written by Caroline Baldwin, the East Area Superintendent for the Polk County School Board. It was she who introduced Starshine into the school board meetings.

But

where, you may be asking, have I heard of the Polk County School

Board before? I looked into my files, and found that back in

1996, the Polk County school system spent nearly $3,000 to buy

three of the glamorous "Quadro Trackers" that were

advertised to locate drugs in school lockers by matching "molecular

emissions" from the substance being sought with identical

emissions recorded on a locator card, or chip. When a Federal

agency lab tested the device, it not only didn't work, but the

"chip" wasn't a chip at all, and held only a few ant

corpses in epoxy. I kid you not. No emissions.

But

where, you may be asking, have I heard of the Polk County School

Board before? I looked into my files, and found that back in

1996, the Polk County school system spent nearly $3,000 to buy

three of the glamorous "Quadro Trackers" that were

advertised to locate drugs in school lockers by matching "molecular

emissions" from the substance being sought with identical

emissions recorded on a locator card, or chip. When a Federal

agency lab tested the device, it not only didn't work, but the

"chip" wasn't a chip at all, and held only a few ant

corpses in epoxy. I kid you not. No emissions.

Due to a statement from the FBI, Polk school

officials were reimbursed $2,865 for three detectors purchased

from Winter Haven private investigator Ray Gillis, who left the

toys with school officials anyway, hoping they'd want to use

them again, despite the lab findings and a restraining order

from the FBI, who closed down the Quadro operation - due to the

JREF tipping them off and supplying data for their decision.

But Gillis continued to use it and believe in it. For all I know,

he still does believe in it.

So what was this device? Simply a fancy dowsing rod - though this one had dead ants - and Angus Williams, Polk schools' director of student discipline, who was convinced it worked, was very disappointed when it was declared a fake. "We were going to try to use it as a tool to deter kids from bringing guns and drugs to school," Williams said. "We thought it worked, but we weren't going to go against the advice of the FBI or federal government."

The school board, on the same day they got the FBI advisory, wisely cancelled a plan to put on a demonstration of the Quadro Tracker. But Madison County Sheriff's Deputy Charles Dickey said his office would keep using the trackers for random drug searches in that north Florida county's seven schools. Can't fool him!

(The Quadro has since been replaced by the "DKL Locator," the same device in a different guise, but this one enthusiastically endorsed by several PhD physicists. Like the Quadro, it was tested by that same Federal agency lab, too, and failed dramatically, but it's still being offered for sale. And those selling it have refused to accept the JREF million-dollar prize, as did the Quadro people. We wonder why....) We must add that Polk and Madison counties weren't the only ones who fell for the Quadro racket. About 1,000 detectors were sold all over the USA to law enforcement agencies, schools, airports and correctional facilities at costs ranging from $395 to $8,000 each, according to an affidavit prepared by the FBI. Judging from that, I think that we taxpayers were the ones who paid for that scam.

I wonder if Madison County will now rush to equal Polk County by hiring their own psychic guru to design their school curriculum? There's such a rivalry between counties here, that they'd better hurry along. A mere $560,000, after all . . .

.............................................................................................

A very interesting book by Fred M. Frohock, "Lives of the Psychics," has just been published by The University of Chicago Press. I was interviewed at length by the author, who appeared to me to be a tad too uncritical of the statements made to him by the "psychics" he interviewed for the book. But that is a matter for discussion another time. I was interested to see that when he looked into scientific work done in the 1800s on spiritualism, all the way forward to the Rhine tests of ESP claims, he recognized that often the scientists could have been deceived by those they were investigating. He wrote:

One problem was that nineteenth-century inquiries into the activities of mediums were controlled primarily by the medium, not the scholar, and so were objects of derision by critics. The tone of these critiques was repeated in the twentieth century by professional magicians like Randi, who scoffed at the gullibility of scientists in allowing Uri Geller to set the conditions for his spoon-bending tricks. The skeptics have been persuasive because the controls in such inquiries were loose, nonexistent, or even worse, in the hands of the subject being tested.

And, though the title of his book is "Lives of the Psychics," and he interviewed many living subjects as well as looking into the records of those long deceased, this is the only reference to Mr. Geller in his entire book! Could fear of litigation have brought on this pointed neglect?

Professor Frohock interviewed a "psychic"

in London, England, named Peter Walker. At the close of the interview,

he opted to have a "reading" done.

At this point in the session I have enough for my research needs. I tell Walker to regard me as a client for the remaining ten minutes of the session. I ask for predictions. He agrees and begins with my children. "You have three children?" I have two. "A boy and a girl?" Two girls. "Well, the eldest must be stronger. There's a very strong personality." He then proceeds to describe my two daughters at length, getting almost everything wrong except the predictions (which, of course, only time can falsify or maintain). Then he turns directly to me and tells me that I will die in my sleep. I ask the obvious: "When?" He answers: "I'm not telling you." Then he does something that at the time I found stunning. He zeroes in on the fact that one side of my family suffers from mental deterioration as they age, a kind of dementia that indeed has caused me some concern as I get older. His assurance is crisp and to the point. He touches his own forehead and says, "You will keep it up here, my friend, until the dying breath, that sharpness." Then he adds another datum. "You take a bit of a nap in the afternoon given the opportunity." He looks at me. "When you pass, it may not be at night."

After a final exchange of views on the afterlife, I thank Walker for an enlightening session. What can we make of these types of sessions (that occur every day, all over the world)? The obvious is probably the least interesting: errors are as frequent as accuracy when observations are matched with actual information. The interesting exercise is decoding the apparent true statements. The one statement that galvanized my attention was the dementia observation and prediction. The man nailed down my one worry about growing old. But when I ran the prediction by my daughters, they were (as the younger said) "underwhelmed." They pointed out that I had presented myself as a professor on a research project, the author of several books. Of course I would reasonably fear a diminution of intellect as I age. Still, Walker caught the problem afflicting only the one side of my family and saw it as confined to only one side. I was impressed, but not convinced.

I offer you the above as an example of how a researcher can embrace a correct guess, amplify its significance, and even enlarge the statement itself to mean much more than the "psychic" ever meant it to mean - though any expansion given to it will be happily tolerated. Professor Frohock, in closing his book, supplies the reader with a list of facts about his life that show clearly how badly the "psychics" he interviewed failed in their readings with him and particularly missed major predictions. We don't often get that data to round out such a book.

Get and read the book. You will find it informative, I promise.

.............................................................................................

We received some 40 correct responses to our "cutting a rug" problem of last week. Matthew Gillie was the first solver. There were several approaches to the matter, all coming to the same conclusion by slightly different means. Angles, slopes, areas, were all invoked. A good and productive response!

The "Randi's Remarkable Rugs" paradox appears in Martin Gardner's 1982 book, "aha! Gotcha" published by W. H. Freeman. To explain the matter, I can do no better than to quote directly from Martin, though this is only a small part of his text on the paradox. In fact, Martin points out that the lengths used - 5, 8, 13, and 21, are four terms in the Fibonacci sequence. I'm not going to get into that, except to say that this series of numbers is named after Leonardo Fibonacci, also know as Leonardo Pisano (Leonardo of Pisa) who lived from about 1170 to 1240 C.E. and was a mathematical prodigy. If you look him up, you'll also learn about how his number sequence expresses the arrangement of sunflower seeds and pine cones. But I digress.

This problem in Martin's book is followed by a second, even more interesting one, which also involves my visiting the bewildered Omar - with yet another rug. I'll leave it to you to look up the book and enjoy the other delightful contents. Writes Martin about the rug problem we are concerned with:

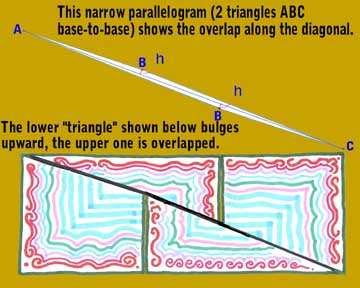

This classic paradox is so startling and hard to explain that it is worth taking time to draw the square on graph paper, cut out the four pieces, and rearrange them to make the rectangle. Unless the pieces are very large, and drawn and cut with extreme precision, you will not notice the tiny overlap along the rectangle's main diagonal. It is this failure of the pieces to fit properly along the diagonal that accounts for the missing square unit of area. If you doubt the existence of this overlap, one way to prove it is to calculate the slope of the rectangle's diagonal and compare it with the slopes of the pieces.

(For a larger image and a better view, click on the illustration)

The obtuse angle ABC of the long, narrow, parallelogram

shown here is 179.4 degrees - thus creating an overlap area that

accounts for the extra square foot of rug that appears to have

vanished. The parallelogram in the illustration is much exaggerated

in the smaller dimension, for clarity. And the re-assembled rug

shows the lower "triangle" overlapping the upper "triangle."

All that's needed is for .6% (one one-hundred-and sixty-eighth)

of the area of the paper model to get lost in the cutting, and

the error will not be discovered. In fact, the height of each

long triangle that makes up the parallelogram - represented by

the tiny red line "h" - is just ½-inch on the

actual rug, and on any diagram you could make on 8½ X

10-inch paper, "h" is just 1/50th of an inch - the

width of a pen-stroke!

The obtuse angle ABC of the long, narrow, parallelogram

shown here is 179.4 degrees - thus creating an overlap area that

accounts for the extra square foot of rug that appears to have

vanished. The parallelogram in the illustration is much exaggerated

in the smaller dimension, for clarity. And the re-assembled rug

shows the lower "triangle" overlapping the upper "triangle."

All that's needed is for .6% (one one-hundred-and sixty-eighth)

of the area of the paper model to get lost in the cutting, and

the error will not be discovered. In fact, the height of each

long triangle that makes up the parallelogram - represented by

the tiny red line "h" - is just ½-inch on the

actual rug, and on any diagram you could make on 8½ X

10-inch paper, "h" is just 1/50th of an inch - the

width of a pen-stroke!

There are carnival/gambling games that either have such a gimmick built into them, or that take advantage of some fact that naturally occurs in the given rules and/or physical materials used. A die - half a pair of dice - for example, can be very slightly off-square, to a point where the discrepancy is not visible to the eye, and that variance can make a substantial difference in the long-term performance of that object. Very slightly rounding an edge or corners, too, can provide an unfair advantage or disadvantage -- over the long run.

The

puzzle posed to you this week involves a representation made

by a dowsing-rod company named DKL -- Dielectrokinetic Laboratories.

They claim that lab tests have established that their device

works. Go to http://www.dklabs.com/labtests.html

and refer to the second set of tests they cite. They label this

set as "Government Laboratory Testing" without naming

the facility that performed those tests. And there's a good reason

for that, as you'll see. It's the same lab mentioned above as

a Federal agency lab . . .

The

puzzle posed to you this week involves a representation made

by a dowsing-rod company named DKL -- Dielectrokinetic Laboratories.

They claim that lab tests have established that their device

works. Go to http://www.dklabs.com/labtests.html

and refer to the second set of tests they cite. They label this

set as "Government Laboratory Testing" without naming

the facility that performed those tests. And there's a good reason

for that, as you'll see. It's the same lab mentioned above as

a Federal agency lab . . .

See if you can figure out just what really happened at these tests, rather than the overall impression you might get from just casually reading what DKL has presented here. This is an excellent example of how spin-doctoring can and will misrepresent the actual data. The "Government Laboratory Testing" as published by DKL has to be very carefully looked at, and your assignment, should you choose to accept it, is to figure out what really happened when the DKL people were tested in March of 1998.

Clues? Well, it was a double-blind test. There were five large opaque containers, and a human target was hidden in one of them, to be detected by the DKL dowsing-rod. The operator was a well-trained person chosen by DKL themselves. One of my contributions to the protocol was similar to a system I worked out for testing dowsers, and was applied in the Kassel tests, described in SWIFT numbers 1 and 2 . . .

Next week, we'll publish the actual results

of those tests. You have a surprise coming. Answer directly to:

76702.3507@CompuServe.com.