My friend Alec Jason, a

forensics expert who was instrumental in my exposure of the tricks

used by Reverend Peter Popoff in his faith-healing swindle, once

shared with me his dismay at the naivety shown by one of the

major authorities in forensics, Vernon J. Geberth. A book

by Geberth titled, "Practical Homicide investigation --

Tactics, Procedures, and

Forensic Techniques, -- begins

a section on "Identification of Suspects" with a definition:

"A psychic is a person who is especially sensitive to nonphysical

forces of life energy."

Geberth depended upon the fatuous claims of Noreen Renier, an Orlando, Florida, "police psychic" who was featured on an episode of the short-lived TV series, "Put to the Test," featuring naive "investigators" who would be unlikely to find a bowling ball in a bathtub in full sunlight. The show did, however, provide an excellent example of just how bad the "readings" of the operators actually are, and how much wishful thinking, enhancement of vague statements, and sheer invention, enter into making the data appear to work.

As Dr. Gary Posner of the Tampa Bay Skeptics pointed out in his review of this program, Renier provided a description of a murderer that was so far off the mark -- except for the gender -- that it would require an incredible amount of imagination to make it fit the perpetrator. As for providing a psychic impression of the crime scene, which was in a small California community, Renier trotted out the usual can't-miss statements. In a stroke of divine inspiration, Renier said about the house, "It seems that there's a lot of white in it." Wow. What more can I say? But there's more: "And there's some strong slant . . . with the roof. . . ." Double wow. How does the woman DO it? Then she offered, "A house, or church, or a house near a church . . ."

The mind boggles at the perception and sensitivity of this inspired psychic. These are facts obviously unknown to her, except by divine insight. The three hosts of "Put to the Test," along with the attending investigator -- who knew all the details of the crime and was dutifully prompting Renier -- were appropriately bowled over. Only on one detail did they express some reservation. Renier ventured: "Screen door creaks." Oops. The screen door scraped the porch, but did not creak. Well, maybe it used to creak. Or it will creak someday. We'll wait and see.

Renier's reading was full of the usual "I feel," "it seems like," "I see," "there would have been," "maybe," "could have been," "I think," and other such expressions. She asked numerous questions. "Is that right?" and "I don't know" shared the same breath. All the way through, the questioners lead her along in her rambling guesses, as well as nodding approvingly when she was right, and looking puzzled when she wasn't.

But there's a good reason for all that feedback, according to Geberth's book. He specifies that ". . . the police have a responsibility to assure that the psychic is properly handled." Apparently that "proper handling" consists of following rules that allow the psychic to operate in an ideal "cold reading" atmosphere, and supplying all the details.

The psychic, he wrote, must be questioned "in a casual, gentle manner," and ". . . there should be no series of ‘Yes' and ‘No' questions. . . . If an answer doesn't sound right, instead of a negative, 'No, no, you're all wrong," [the psychic prefers] 'Let's go back to that later.'" And, the expert adds, "Psychics respond better and are more accurate when the individuals working with them have a positive attitude."

Geberth suggests that to ascertain the authenticity of a psychic, a good method is to depend upon word-of-mouth. "This report [about how good the psychic is] may appear in a local newspaper . . ." he tells us. Sounds dependable enough for me!

On the rational side of

his description on how to handle psychics, the author goes on

to actually suggest several rather good methods of avoiding giving

data to the psychic, and yet misses the importance of taping

the session. To his mind, taping should be done only in

order that none of the details offered will be lost; in my opinion,

the astute investigator might

wish to tape a session in

order to record the entire gamut of details, the real precision

of the statements, and the wild range and number of guesses,

right and wrong. From taped records, such facts are invariably

evident.

Geberth warns his reader that an unusually accurate performance by a psychic should be regarded with suspicion:

The phonies like conditions they can control. They

do a lot of key bending and blindfold tricks that are

impressive. Their clarity and accuracy are usually

overwhelming. . . . Real psychics are human, and

therefore are subject to error.

But fakes are not human.....? Are they divine, then?

And this man is an expert in "practical homicide investigation." Did he have anything to do with the O.J. case?

In closing his naive reference to police psychics, Geberth writes:

. . . there is a definite need for the evaluation of the

successes and failures of psychic phenomena as

they relate to law enforcement before they can be

recognized as a "legitimate" investigative tool.

Grammar aside, I believe he meant to write "psychics" rather than "psychic phenomena," and he seems unaware of Dr. Martin Reiser's rather definitive and damning evaluations, in 1979 and 1982, of whether law enforcement agencies could benefit from employing psychics, and the in-depth examination by Piet Hein Hoebens in 1981 of Dutch psychics Gerald Croiset and Peter Hurkos, inarguably two of the best-known practitioners of this flummery. Reiser concluded, after a comprehensive test he performed on a dozen police psychics:

Overall, little, if any, information was elicited from

the twelve psychic participants that would provide

material helpful in the investigation of the major

crimes in question. . . . We are forced to conclude,

based upon our results, that the usefulness of

psychics as an aid in criminal investigation has not

been validated.

The evaluation Geberth called for has already been done.

He also wrote that:

The police have much to learn about the relative

value of psychic phenomena in criminal

investigations.

He might have better written that:

The police have much to learn about how their own

evaluation of psychics can be colored by wishful

thinking and their willingness to believe that these

abilities have been established as genuine.

..................................................

In the '60s, while I was involved in my all-night radio show out of New York city, I was invited by an ardent believer to witness a performance of "psychometry" by Florence Sternfels, another "police psychic" from Edgewater, New Jersey. Psychometry is the claimed ability to handle an object and to then describe by psychic means the history of the object and its owners. And I was invited to bring along with me a test object with some sort of history.

Florence had made a bit of news when she tricked the phone company into giving her a listing that they were unwilling to allow. She had a private phone, but wanted to be listed as "Florence the Psychic," and the company insisted that she take a (more expensive) business listing. She simply took a private line and listed her name as "Psychic Florence," which got her listed in the white pages as, "Florence Psychic." And that satisfied her needs.

I showed up at a huge home in Croton-on-Hudson with an envelope containing an object about which I actually knew nothing, in fact I'd not even opened the well-padded envelope. It was an object that had been loaned to me by Walter B. Gibson, creator of the fictional Shadow character that was at one time so popular, and a man who had known most of the major figures in the magic profession. I knew nothing about the object, so that the test would be appropriately "blinded." Walter was standing by at his telephone awaiting a call from me so that he could reveal the history of his test item.

After Florence had given

several "readings" on offered objects, pumping the

owners for information as expected and thus scoring strongly

to the delight of the faithful fans present, it came my turn.

I gave her my test object, and I told her that I knew nothing

about it, but that I could make a phone call -- after her reading

-- to learn everything I needed to know about it.

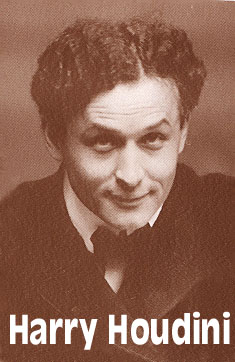

However, as soon as she shook from the envelope a man's well-worn and very old-fashioned silver belt buckle engraved with the initials "H.H.," I rather guessed who the owner had been, and I had to work hard to avoid her reading my reactions to anything she said.

It did not appear that

the psychic looked at the object at all, but I'd noticed that

she always gave each item a quick look and turned it over while

making a few disconnected comments, then held it tightly in her

hand, out of sight. "This belonged to a man,"

Florence began. That was very obviously true, but I said

nothing. "Did it?" she asked me. "I don't

know," I answered. "Oh.

I get the initials H.H." she said, staring off into space,

then she held the buckle close to her face and squinted at it,

as if she had a hard time focusing in on it. "Ah!"

she exclaimed, "Look at this! Those are the initials

right here on it!" She showed it around to a few seated

near her, and received appropriate awed verification of her

insight. She turned

to me. "I get that this man is in spirit."

That style of belt-buckle was clearly from half-a-century back,

but I did not react. "Is he in spirit?" she asked.

"I don't know," I replied. Florence looked unhappy.

Much fingering and turning of the belt buckle ensued. "Politics?" she ventured. I was silent. "Or maybe the military, in some way?" No reaction from me. "Was he in politics, or in the military, at any time?" she asked. "Florence," I replied, "I know nothing about this object. It's a test object."

"You don't know anything about this buckle?" she said as she angrily rose from her chair. "That's right," I told her. "Well-how-the-hell-am-I-supposed-to-know, then?" she screeched, and threw the silver buckle down on the thick rug at my feet.

There it was, from her own lips, a succinct statement of just how she operated. I left the room, with Florence mumbling and complaining to the crowd, phoned Walter and verified my suspicion that the belt buckle had belonged to Harry Houdini, and I discovered that it had been worn by him in October of 1926 when he entered Grace Hospital in Chicago to be treated for the ailment that did him in ten days later. When I returned to the waiting audience and informed them of these facts, Florence immediately came up with, "You see, I knew there was serious sickness involved with this object, and that always dulls my sensitivity, because I feel the pain." I quickly asked her where the pain was, and while transfixing me with a hard look, she pointed to her chest. "Really?" I remarked, "It was appendicitis that killed Houdini." "He also had a heart condition!" she snapped, and my reading was most definitely over.

Perhaps Houdini -- or Florence Sternfels -- had a misplaced vermiform appendix . . . ?

Postscript: At JREF,

we've just received a comprehensive report from The

Rationalists of East Tennessee

(RET), who at our request recently performed

the required preliminary examination

of an applicant for the million dollar

prize that we offer.

As you may know, no person has yet passed the

preliminary test and gone

on to be formally tested. That situation has not

altered as a result of the

RET report. Following a strict protocol, and

adjusting all of the terms

to satisfy the dowser who had made the

application, the Tennessee

group carried out an exemplary series of tests

that will be discussed shortly

here on this page.