(I must comment here that if any Aussie dowser had passed Bob's test, that person would have passed the preliminary test for the JREF million-dollar prize application, as well!)

Thanks, Bob. (One small caveat, if I may. Upon the "nudging" of the bottles, noted above, I would have immediately closed down the operation and started again. One cannot leave holes in the procedure that are then dragged in as excuses, by either side, in such a confrontation.) This report meets expectations, to say the least. It fits with all other comprehensive tests that have been done of dowsing, and is done properly and fairly. Note that there were the usual raft of excuses and alibis following the failures. One point that is not followed up on, is the post-post-trial rationalizations. Though the dowsers, by Bob's account, agreed that the test had been properly and fairly carried out, I'm pretty sure that upon careful reflection they were able to discover other unsuspected flaws in the procedure that inhibited their abilities.

The flaw is in their presumptions. They just can't do it.....

So, we're ready for nominations for the Annual JREF Pigasus Awards, given annually on April 1st in these categories:

If you have candidates to nominate, please e-mail them to randi@randi.org, and put PIGASUS AWARDS in the subject line.

Stealing from a widely-circulated proposed "Bill of Rights For Physicists" I have prepared this document for another field of scientific endeavor. I trust that those of my friends who are involved in this field, will forgive my little joke — though there are some in the business who fit these specifications very closely and would endorse this document....

The Parapsychologist's Bill of Rights

We hold these postulates to be intuitively obvious: that all parapsychologists were born equal and infallible (to a first approximation), and were endowed by their creator with certain special rights associated with scientific rules and standards. Among these are sumptuous grants, n degrees of freedom in interpretation of trivial results, and the vigorous pursuit of nonsense, especially if federally-funded. We also reserve the following rights, which are invariant under all linear transformations:

I. To reduce all observed situations where miracles are involved, to ideal conditions of honesty, innocence, and naivety.

2. To use order-of-magnitude calculations whenever necessary, and to otherwise adjust data to accommodate obvious truths.

3. To dismiss any methods of observation or analysis which deny the preferred result, as "unacceptable," "nasty," "badly behaved" and "untypical."

4. To invoke the Uncertainty Principle and/or the Shyness Effect when challenged by confused mathematicians, electrical engineers, physicists, and other real scientists.

5. When pressed by non-parapsychologists for an explanation of (4) to mumble about scientifically naive, uninformed, insistent, skeptics.

6. To enthusiastically embrace "meta-analysis" when all experimental procedures have failed to provide any real significance, and when further funding therefore appears to be in doubt.

7. To justify a shaky reasoning process by observing that it does happen to give an answer that the media will accept and publicize, to the glory of parapsychology.

8. To use plausibility and metaphysical arguments in place of proofs, and thenceforth to refer to these arguments as firmly established proofs.

9. To instantly take on faith any principle which just seems right but can't actually be proven.

10. When confronted with a question which requires any thought at all, to reply, "Why not? These are mystical matters that only we understand!"

11. In response to all direct confrontations from skeptics, to employ obfuscation, dismissal, and Ivory-Tower stances.

12. To refuse to discuss the JREF million-dollar prize as a matter beneath the dignity of an academic, while hoping that the word "Nobel" is not brought into the discussion.

The Role of the Conjurer in Psi Research

The late science-fiction author Lester Del Rey was accustomed to declaring authoritatively on every subject from oenology to onomancy. He was so bold as to have his business card imprinted with the single modifier "Expert." And I suspect he could support that claim upon demand.

We all have need of expert advice and assistance in our daily lives, on both a personal and a professional level. As highly trained and experienced as he is, I have known my dentist to step to the telephone and ask a distant colleague about some aspect of his craft — while I recline in his chair with a mouth full of tubes, cotton wads, and assorted bits of hardware. But I respect his need and his wisdom in reaching out for advice in order to function more efficiently.

Consider: I doubt that many readers recognized the words oenology and onomancy, which I used above. To resolve that small problem, you can turn to a dictionary. You need not feel like a simpleton in order to do so. Very well educated and intelligent people have quite thick, comprehensive, and well-thumbed dictionaries available to them. Such reference tools — and the recognition that they are necessary — enable us to live and work more effectively.

A little boy once went to the public library and asked the librarian for a book about penguins. He was given a book, he took it away with him, and he returned the next day. The librarian asked him if it had served his purpose. "This book," said the boy, "told me more about penguins than I needed to know." Obviously, there is a need for discrimination in seeking out and accepting expertise. One need not know the life history of Henry Ford in order to adjust an Edsel carburetor. But without reference to the appropriate manual such an adjustment becomes hit-or-miss where it could be a straightforward procedure.

Parapsychologists are very much in need of a certain type of expert help. Frequently involved in designing and implementing tests for ESP, precognition, psychokinesis, and other unlikely — but not impossible — abilities, they are sometimes faced with human subjects who are able to deceive them by bypassing controls and outwitting these academics who are dealing with factors they do not normally encounter and are thus understandably inexperienced and inexpert observers in this field. The subject is chock full of examples of this problem, and it is still an active factor in paranormal research.

In the 1920s, when Dr. Joseph Banks Rhine introduced a statistical approach to the very new study of parapsychology, orthodox scientists were able at least to express their willingness to consider the paranormalists' claims. But the dramatic impact of such novelties as "spoonbending," for example, proved far too tempting for some incautious parapsychologists and an army of bumbling amateurs. They saw Nobel prizes in the breakthroughs revealed by individuals who appeared to exhibit marvelous supernatural abilities, and they abandoned the statistical, systematic methods introduced and encouraged by Rhine — though he, too, was quite beguiled by "star" performers. High-profile members of the parapsychological elite began agitating for a return to the study of "gifted subjects," an approach which gives immediate gratification, much better media coverage, and of course governmental and private funding impetus. This set the entire movement back decades.

But by that point, even Rhine's work was beginning to lose its former luster. Critics were able to show that his findings were somewhat less than compelling and that his protocols had not only been bypassed but had been insufficiently developed to guard against a number of now-obvious pitfalls. Today, Rhine's work is largely looked upon as well-meaning but somewhat naively conducted. He was the pioneer, and he made the mistakes that are inevitable in any new area of science.

In 1978, convinced that the parapsychologists needed to be shocked back to reality, I set in motion an experiment that I named "Project Alpha." For years I had been urging parapsychologists to recognize that the expert advice of a qualified conjurer is an absolutely necessary part of designing an experiment in which there is a possibility of deliberate trickery on the part of either the subject or the experimenter. This message had been ignored. Several researchers had firmly declared that (to quote one of them) "magicians must not be put in charge of experiments!" Of course I had not suggested that at all, and I enthusiastically agreed. I firmly believed then, and do now, that a conjurer's participation in any scientific endeavor must be limited to his narrow — but important — spectrum of expertise.

At that time, I had in my files letters from two young would-be conjurers who had expressed their availability should a situation arise in which I might demonstrate that scientists can be easily deceived. When an Associated Press news release announced that a physics professor/parapsychologist at Washington University in St. Louis, Missouri, had been given $500,000 to study "spoon-bending children," I realized that the ideal opportunity had arrived. First I wrote to the parapsychologist to advise him that I was available to him for consultation on any experimental design or implementation, free of any obligation of payment or acknowledgment. By return mail I was informed, in effect, that he could manage quite well without a conjurer.

At my suggestion, the two boys — 17 and 18 years old at the time — contacted the laboratory in St. Louis and provided stories to fit the expectations of the scientists there. Some parapsychologists prefer to believe that "gifted subjects" become psychic when exposed to trauma of some sort, so one "mole" said he had received an electric shock while still in utero, after which his psychic powers became evident. The other said that he was unable to go near a rat-trap without setting it off. Both of them were accepted into the lab on the strength of their stories, and were tested for a total of 160 hours over the next three-and-a-half years on week-ends and during school holidays.

Fooling the scientists proved very easy. Using as a guide the general tactics employed by other kids when they had been tested by scientists, both Alpha subjects produced "spirit"photos on Polaroid film, bent spoons, keys, and coat-hangers, turned tiny propellers inside bell-jars, moved objects around on a table, traced cryptic messages in ground coffee sealed in an upturned fish tank, caused ghostly inscriptions to appear on paper sealed in glass jars, and in general convinced the researchers that they were bundles of psychic energy. They did it by bullying the experimenters into doing things their way or not at all. The mice were running the experiments.

When the Washington University staff initially reported to their colleagues on this remarkable series of miracles, they wrote that many varieties of psycho-kinetic results had been obtained in their lab. They even presented a slide show and a videotape to prove their case. But when I was at last allowed to participate by providing them with a videotape of admittedly faked psychic trickery — some of which had been used by the Alpha subjects in the Washington University tape — the written report was hastily recalled and modifiers like "purportedly" and 'apparent" were inserted into the formerly naive account. Most importantly, following my initial participation, I was able to demonstrate to these researchers certain weaknesses in their control techniques. At this late date, they implemented my recommendations, and the Alpha boys were no longer able to fool them. The experiments ceased.

Finally, we terminated our Alpha experiment by exposing the ruse in the media, and Looking-Glass Land was in a turmoil. After things settled down, the official organization of psychic researchers, the Parapsychological Association (PA), issued an advisory to its members stating that, in cases where subjects might be able to affect test results by some sort of subterfuge, the use of an experienced conjurer as an advisor would be a wise move. Almost immediately, two prominent parapsychologists contacted me, and I suggested adequate protocol for an upcoming experiment they were planning. A few weeks later, they reported that this amendment to their protocol had resulted in exposure of a psychic faker in one lab. Project Alpha had paid off.

The Alpha experiment was remarkably well received by some of the PA members. It had consisted of planting two "moles" in an exceedingly well-funded parapsychology lab to see if the researchers were really as naive as they seemed. They were. As a result, we could have hoped that future experiments would be better controlled. Apparently the Alpha vibrations have now died away, and tentative approaches to the conjuring profession seem to wither before being put into operation. A recent promise of data from the University of Arizona is now dead, and agreements by psychics to show up for testing — even with the "carrot" of the JREF's million-dollar prize — have been ignored. One must wonder why.

Now it must be recognized that not all involvement of magicians in parapsychology has proven useful; there have been minor disasters in this regard. Wide-eyed psientists in Europe have in several cases called in amateur (and professional) conjurers to witness "psychics" at work, only to hear from their "experts" that the phenomena exhibited are genuine — when other magicians saw quite obvious and well-established trade methods being employed.

What, then, is the definition of a "qualified conjurer"? Since conjuring is essentially (of necessity) a "closed" profession, it is not readily obvious to observers what criteria should be sought in an advisor. First, let us define our terms. A "magician" is one who performs "magic." My preferred definition of "magic"is: "Using spells and incantations to control the forces of Nature." Let me assure you that all the spelling and incanting you can muster will not find a chosen card in a deck, nor will it materialize a bunny in an empty hat. For those ends, we employ chicanery and allied methods. The dictionary tells us that the correct term for my profession is conjuring. Properly, then, I am a conjurer, 'One who uses trickery to simulate magic."

As a professional conjurer for almost six decades, I can tell you that there are three general classes of persons associated with my calling. They are: (1) amateur conjurers, (2) people who do tricks very, very well, and (3) master conjurers. The first group, to me, are welcome colleagues so long as they remain aware of the meaning of the word amateur. It derives from the French and means, in this connection, "one who loves conjuring." But, with rare exceptions, I would not consider amateurs as suitable advisors in parapsychological matters. One faulty conception they have is that their duplication of a "psychic" trick proves that the faker used the same means. Of course it does not. It merely demonstrates that such a trick is easily done. That fact is of limited value.

Admittedly, the second category includes some of the very finest, most convincing and entertaining performers. Most are full-time artists and make up the largest proportion of what the public recognizes as professional magicians. Their repertoires, however, are often strictly limited to the requirements of their performances. They have what the trade calls "an act." It is usually a finely-honed and highly professional presentation. But the artist, in many cases, does not go beneath the surface to understand the psychology or even the sometimes esoteric technology of the art — nor is such knowledge needed. Such an artist performs by instinct, learned from long experience. Does a virtuoso violinist need to design or construct violins?

I must make one further comment to prepare you for my eventual point. My students are always taught one important fact: Audiences do not go to see "the tricks," though they may have that initial intention. They go to see 'the person." It is the Wizard, the Magician, the Personality that they enjoy. And that conjurer performs a trick. To continue my analogy, I go to see and hear ltzhak Perlman playing the Mendelssohn Violin Concerto, Opus 64; I do not go only to see and hear the Mendelssohn Concerto.

The third class I have designated above — the Master Conjurers — are persons you may never have heard of but who not only can perform (in some cases, with such diabolical dexterity that it makes my eyes water with jealousy!) but who also understand thoroughly the nuances of the art, down to the almost subliminal perception of the movement of a spectator's eye. But they are aware of their perception; it is not merely an instinctive reaction. They, and they alone, are qualified to serve as advisors to responsible parapsychologists who earnestly wish to impose strict controls over their subjects. I am proud to know that many of those in my profession include me with Conjurers of the Third Kind.

Mind you, I have found that many parapsychologists seem to believe that a positive result obtained under loose conditions is vastly preferable to a negative one resulting from proper controls. The scientific method calls for the gathering of evidence, the examination of that evidence, the formulation of a theory to explain it, and the testing of that theory. It does not permit the gathering of evidence to prove a favorite idea.

The three general classes of conjurers I have specified above are, of course, not necessarily distinct from one another. Unfortunately, though for reasons that are obvious to astute observers, the Parapsychological Association specified in their directive following Project Alpha that consultant conjurers must be chosen from among members of certain fraternal organizations in the United States that claim the vast majority of their members from the first class of conjurers I have designated. Since, at that time, I did not — by choice — belong to those organizations, it was felt that I thus would be excluded from consideration by any serious investigators. The unkind thought even passed through my mind, that certain persons in the PA might have designed that qualification to specifically exclude me. However, as reported above, two prominent parapsychologists asked for my assistance. Then, within two weeks, three more applied. It is encouraging to see that some parapsychologists responded to the suggestion that they may need expert assistance. There are at present some notable researchers who have ignored that PA advisory and believe that they are simply too smart to be deceived. This is a dangerous philosophy. Such thinking leads to many spurious sales of the Brooklyn Bridge every year.

There is, however, a form of deception against which the combined talents of scientists and conjurers may be powerless. It is self-deception. Benjamin Franklin remarked, "There are no worse liars than quacks — except for their patients." Substitute "frauds" for "quacks" and "victims" for "patients" and you will see my point. The victims of so-called psychics are prone to lie or waffle about the miracles they have seen, often believing what they say either because they have reconstructed the events incorrectly or because they feel that a little gloss cannot hurt the story of their experimental results. In either case, they are fooling themselves. This tendency can go to extreme lengths. Parascientists have even said that people like myself and Martin Gardner, a well-known critic of parapsychology, are motivated mainly by our own private fear of the unknown. To coin a phrase, "fat chance."

The tendency to self-deception is pervasive. For example, one dupe of Project Alpha continued for years before his death to believe that those "moles" performed genuine miracles, even after their detailed confessions. There is no remedy for such masochism.

Frequently, the "psychics" have proven to be highly entertaining, as well as provocative. This is a characteristic of the conjuror as well, of course. As an example: one of the basic tricks for the card manipulator has always been the find-the-chosen-card effect. In essence, a spectator selects a card (by physically drawing it from the pack, mentally choosing it, naming one at random, or by other means) and it is then discovered by the conjurer (by being named, physically located, found in a pocket, etc.). The process is generally recognized as a conjuring trick, especially if the performer is dressed in a tuxedo and is known as "The Great Balsamo" or another euphonious title. However, it is evident that if someone who does not claim any manipulatory skill were to be able to perform the find-the-chosen-card effect without resorting to trickery, it would upset every notion of the universe as we know it. Suppose that person were only able to demonstrate an ability to divine — with a degree of statistical significance — the color (red or black) of a playing card. As entertainment, that routine is a loser; as a laboratory project, it's a big winner. Spoon- and key-bending tricks are of that nature, but unless you believe they are genuine examples of supernatural powers, they are pretty poor theater. Spoonbenders claiming supernatural powers have been able to draw huge crowds of people who would never have paid to see the Great Balsamo mangle cutlery, but who will trample one another to witness a "psychic" doing it.

Some scientists are drawn into that net, too. They choose to make the same error that many of their colleagues — in other fields of science, as well — have made. They say: (1) I am intelligent. (2) I am well-educated. (3) I am a good observer. Therefore: Anything I see and do not understand is supernatural. Wrong. What they regard as supernatural may very well be the result of using those three facts against them. This is in accord with the very basics employed by the conjurer to deceive his audience. The smarter they think they are, the harder they fall.

Children, as has often been said, are very difficult for the conjurer to fool. They simply lack the sophistication of adults, and they are therefore not prepared to presume the simple, basic facts that we must presume every day. Their experience of the world is not sufficient for them to be fooled! The conjurer can casually drop a cardboard box upon a chair and, because it sounds empty, he need not show that it is empty, for the adult audience. The child, not yet familiar with the sound of an empty box in contrast to the sound of a box containing something, needs to be shown. It is also a fact that the audience, subconsciously assuming the box to be empty, is more convinced of that fact than if they had been directly shown or told that it was empty. Adults tend to believe what they are allowed to assume for themselves, much more than what is specifically pointed out to them. ("Methinks he doth protest too much . . .")

I recall that, when I was a child in Canada, a certain company who made baking powder adopted a rather clever ruse to degrade the competition. They announced, "Our product is made without the use of alum!" and they immediately won over my mother as a customer. When I asked her if the other manufacturers put alum in their baking powder, she was a bit puzzled by my question. She had merely made an unconscious assumption that they did. This very gambit is well known to conjurers, and to "psychics" as well. One popular American "mentalist" is heard to declare, "Why, if I wanted to, I could perform all of these demonstrations by trickery!" And the audience jumps into the trap by assuming that at least some of his items are not performed by trickery. Wrong.

A parapsychologist, by my definition, is one who, seated in the park near a riding academy and hearing hoofbeats approaching, expects a unicorn to round the corner. He is surprised and disappointed when he sees a horse come into view. No matter how well motivated, these researchers cannot afford to entertain such expectations. They must follow the rather unglamourous procedures their colleagues in other disciplines insist upon. Otherwise, their complaints about a lack of acceptance by their peers cannot be heard.

Expert advice and involvement is available to serious researchers in the field of paranormal research. They would do well to take advantage of it; if they do not, they may find themselves in the company of the rather large number of academics who have learned, too late, of their own vulnerability.

Yes, expect a horse. But please, recognize a unicorn if it shows up.

Next week, an interesting piece by Dorion Sagan, just back from the trip to China that I was unable to make back in December. Dorion is a science writer who has carried on the tradition so well established by his illustrious father. You'll enjoy this.....

My buddy Bob Nixon is an enthusiastic member of the Australian Skeptics. After a few long conversations with me during a meeting last August in Australia, when I tested a dowser/applicant for the JREF million-dollar prize, Bob was inspired to organize a new test of dowsing claims, and the decision was reached to make this an annual event. The results are not surprising, but we're happy to see that dowsing/divining claims are still being regularly challenged Down Under.

My buddy Bob Nixon is an enthusiastic member of the Australian Skeptics. After a few long conversations with me during a meeting last August in Australia, when I tested a dowser/applicant for the JREF million-dollar prize, Bob was inspired to organize a new test of dowsing claims, and the decision was reached to make this an annual event. The results are not surprising, but we're happy to see that dowsing/divining claims are still being regularly challenged Down Under.

Please, no more pigs! Over the holiday season we were inundated with the pictured novelty, a Flying Pig toy. Oh, it's fun, flapping its wings and soaring around on a tether, and we're grateful for all of you who were kind enough to send us one, but when the count got up to 30, it became an epidemic! We now have all the little critters that we can ever use, and they will be sent out this year as prizes for our annual Pigasus Awards — which we unfortunately missed last April.

Please, no more pigs! Over the holiday season we were inundated with the pictured novelty, a Flying Pig toy. Oh, it's fun, flapping its wings and soaring around on a tether, and we're grateful for all of you who were kind enough to send us one, but when the count got up to 30, it became an epidemic! We now have all the little critters that we can ever use, and they will be sent out this year as prizes for our annual Pigasus Awards — which we unfortunately missed last April.

This is an opportunity to respond to those who ask, contemptuously, what a magician could possibly contribute to science and/or scientific investigation. Without a serious academic degree, how would a mere conjuror be able to properly give information to a real scientist? I wrote this some years ago for a magazine....

This is an opportunity to respond to those who ask, contemptuously, what a magician could possibly contribute to science and/or scientific investigation. Without a serious academic degree, how would a mere conjuror be able to properly give information to a real scientist? I wrote this some years ago for a magazine....

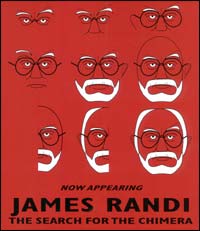

Sometimes I'm a little slow to "get" things. In 1999, I had the pleasure of lecturing for the University of Minnesota Graduate School, as one of the Guy Stanton Ford Memorial speakers. They printed up a doozy of a poster to advertise the event, and it's one of my very favorites. Showing it to a visitor last week, I suddenly "got the point" of the artist. See if you can perceive what so long escaped me....

Sometimes I'm a little slow to "get" things. In 1999, I had the pleasure of lecturing for the University of Minnesota Graduate School, as one of the Guy Stanton Ford Memorial speakers. They printed up a doozy of a poster to advertise the event, and it's one of my very favorites. Showing it to a visitor last week, I suddenly "got the point" of the artist. See if you can perceive what so long escaped me....