Andrew Opines, Over-Enthusiasm for Evidence, The Surds Are Coming! The Surds Are Coming!, Entrance to Hell Discovered, and Feynman on Cargo Cult Science........

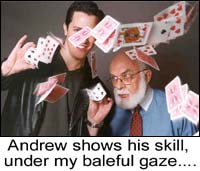

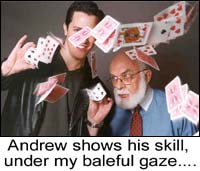

Our colleague Andrew Harter, an accomplished magician in his own right, is the man who handles the truckloads of applications that continue to pour in at the JREF, regarding our million-dollar challenge. Last year, when the "Masked Magician" showed up on the Fox-TV network purporting to reveal the major secrets of the professional magician's act, Andrew and I began receiving inquiries from the media and from magicians who wanted our "take" on the situation. I simply dismissed the dismal matter as a mean-spirited, desperate reach for ratings, and predicted — correctly — that the effort would pass largely un-noticed and would be much less damaging than many of our magician friends had feared. Andrew made a deeper analysis of the situation, which I share with you here....

Our colleague Andrew Harter, an accomplished magician in his own right, is the man who handles the truckloads of applications that continue to pour in at the JREF, regarding our million-dollar challenge. Last year, when the "Masked Magician" showed up on the Fox-TV network purporting to reveal the major secrets of the professional magician's act, Andrew and I began receiving inquiries from the media and from magicians who wanted our "take" on the situation. I simply dismissed the dismal matter as a mean-spirited, desperate reach for ratings, and predicted — correctly — that the effort would pass largely un-noticed and would be much less damaging than many of our magician friends had feared. Andrew made a deeper analysis of the situation, which I share with you here....

While I agree with some of [another magician's] points, I disagree with several others. FOX's exposure of magic is no more in the tradition of Walter Gibson's writings on magic [Gibson, creator of "The Shadow" character, wrote from time to time giving secrets of magic tricks] than the FLINTSTONES is an extension of the field of paleontology.

Magic is an art that requires patience. Those who don't have the patience to sit down and try to read a book on the subject or spend the time necessary to master its principles are not likely to get anything more out of FOX's exposure than the brief titillating sensation an adolescent may get by catching stray bits of nudity on a scrambled cable channel.

As a lecturer, I've learned that the greatest strength in using magic to educate an audience comes from performing an effect and leaving them with no explanation. Otherwise, people tend to overestimate their critical abilities and assume that they were only moments away from solving the effect before it was revealed to them.

For the few that believe that Copperfield can truly fly and that Penn really drowns Teller, no exposure will sway them from their beliefs. They've spent a considerable amount of time learning to ignore that which doesn't support their fragile view of the universe. It's doubtful some masked exhibitionist is going to have an impact on their lives — other than to cheapen a form of entertainment upon which many people depend for their living.

Well said, Andrew. Your exposure to the sometimes ridiculous claims that arrive at your desk, equips you very well to give an expert view of just how poorly so many people think about the real world in which they live.

Flipping through TV channels on New Year’s Day, I found my expectations both met and shattered. On CBS, both John Rennie of Scientific American Magazine, and Bill Nye "the Science Guy," were interviewed on the future of science and technology, and between them they gave a lucid, simplified, view of nanotechnology and other valid and fascinating aspects of what’s probably coming into our lives in the next few decades.

Flipping through TV channels on New Year’s Day, I found my expectations both met and shattered. On CBS, both John Rennie of Scientific American Magazine, and Bill Nye "the Science Guy," were interviewed on the future of science and technology, and between them they gave a lucid, simplified, view of nanotechnology and other valid and fascinating aspects of what’s probably coming into our lives in the next few decades.

Going to Fox-TV at the same time, I found two astrologers I’d never heard of, and our own Sylvia Browne (who just cracked 123 days in her stonewalling of our agreement; way to go, Sylvia!) enthusiastically discussing predictions that really matter, the latest who’ll-marry-whom aspects of Glittertown politics, especially Tom Cruise’s amorous adventures, and a wide-eyed host oohed and aaahed appropriately as these weighty matters were revealed to us with the usual accuracy and details. What disdain and contempt Fox-TV must have for their viewers! Browne essentially said nothing, but sat there with her trademark pained expression and mouthed some generalities. Yawn.

Later that day, I tuned in to National Public Radio (NPR) and heard Graham Molitor of the World Future Society being interviewed. Mr. Molitor came out with an unfortunate remark, saying that his methods of calling the future, unlike "peering into a crystal ball, examining tea-leaves or the entrails of birds, [was] much more scientific." Anything is more scientific than these methods, sir! And when Mr. Molitor referred mysteriously to accelerating light beyond the known limit (300,00 km/sec or 186,000 miles/sec — in vacuo) "by a factor of one to six," and pointed out in support of that idea how at one time, the speed of sound (330 m/sec or 1100 ft/sec in air) was thought to be the limit at which an aircraft could travel — the "sound barrier" — I had to reserve my opinion about his scientific acumen. But the gem of redundancy was the title of the program: "Predictions for the Future." Just who writes these things.....?

We happily run this next essay by professional portrait photographer William McEwen, as part of our "visiting author" feature, introduced to accommodate those who have contributed articles for the original printed version of SWIFT, which is now this on-line publication you're reading. This piece by William illustrates very well the fact that people can overextend their interpretations of data presented to them, a matter of great interest to us at JREF since it addresses one of the main features of how people are deceived by their own enthusiasm in finding meaning where often there is none.

I recall that many years ago I attended an advance screening of an avant-garde film in New York's Greenwich Village, where I lived at the time. Leaving the theater, I was amused to hear two enthusiastic fans of the producer exulting over one of the hidden messages they were sure he'd dropped into the film. There were a few scenes that had been shot inside a hayloft, and those were shown in black-and-white, in contrast to the rest, which was in full color. The two fans remarked on the subtle use of B&W photography in scenes "where he didn't want the outside world to intrude on the secret world of the children." I didn't have the heart to explain to them that actually the producer had run out of money, and could not afford to light the interior shots where the natural lighting didn't quite provide enough detail for his needs. He'd turned to much cheaper B&W film stock only to save money, not to produce an arty effect. I knew this because I'd interviewed him on my radio program the week before....

Subjected to "psychic" readings by the flummery artists who purport to speak with the dead, victims are very prone to hyperbolize and invent details that just aren't there in the "20 Questions" game being played. Photographer McEwen shows us here that his profession, too, is subject to "creative" observation.....

Something from Nothing: Reading Things into Portrait Photographs

I have been a photographer for a long time, and for the last six years, I've concentrated exclusively on portraiture. It is one of the greatest jobs around. I get to meet and spend time with interesting people and record their faces for the future. I am very fortunate to have the opportunity to spend my time this way.

As a portrait photographer, it's my responsibility to record what someone looks like, and if I do my job well, the person, the background, the light, and the composition will all work well together visually to create an interesting whole. There's no more to it than that.

But to my bewilderment, the audience sometimes sees more. They see things that aren't there, and they make all sorts of interpretations. Here is a perfect example. Last year, someone e-mailed me about my photograph of Dallas Mayor Ron Kirk. "I understand exactly what you were saying in that picture," he wrote.

Huh? What I was "saying?" I wasn't saying anything. I just used my camera to make a photograph of what the man looked like. I told Mayor Kirk to stand over there, I moved my camera around until everything looked good, and then click, I recorded it on a sheet of film. No statement, no interpretation. Just reality. A man and his surroundings.

Once, while I was speaking with high school students at a museum exhibition of my portraits, one young man looked at my picture of orchestra conductor Keri-Lynn Wilson and said, "The way her arms are folded in front of her shows she was uncomfortable." Quite the contrary. Keri-Lynn and I had hit it off, and we spent most of the photo session laughing. For the picture that ended up in the exhibition, I had merely asked her to do something interesting with her arms. She folded them in front of her, and click, I made the picture.

I'm certainly not the only photographer to have fallen victim to people interpreting their work, seeing something where there is nothing. A good source of people reading all sorts of things into photographs is the PBS-TV American Masters special about the portrait photographer Richard Avedon. Referring to Avedon's picture of the writer Dorothy Parker, the singer/actress Andrea Marcovicci said:

She [Parker] looks like every bit of wit that she ever had, had just left her a second before that photograph was taken. And I know what he [Avedon] must have been doing. He must have been contrasting one of the world's greatest wits, one of the greatest wisecrackers and a person who really knew how to have a good time, with their darker side. And he preserved forever an image of some inner truth of what she really had to go through in life.

To this observer, looking objectively, it appears that Avedon simply stood Parker against a gray wall and clicked the shutter.

I once photographed a prominent Dallas businessman. When I showed the prints to his wife, she was elated. "You really captured his personality," she told me. That was a nice compliment, but in my opinion, without merit. Can a photograph capture a personality? I don't think so. If anything, she merely recognized an expression she had seen countless times during many decades of marriage.

Photographer Duane Michals, in his book "Album," gets it right. He writes:

Some photographers can be very presumptuous in their self delusions about "capturing" another person with their cameras. I know of no one who actually believes that he reveals the soul of his sitters with his photographs of them. What you see is what there is.

Agreed. A personality is just too complex to capture in one photograph. When we photographers are told that a specific photograph doesn't do the subject justice, I think most often it is because the personality cannot transfer into a photograph. With many, charisma or charm plays a key role in his or her attractiveness. When charisma or charm is extracted from their presence by a photograph, we evaluate the subject, perhaps for the first time, on purely visual terms.

That is not to say that a camera is incapable of recording emotion, or at least the appearance of emotion. For this article, I am referring only to collaborative portrait sittings, not photographs made by news photographers. The pictures that we see in newspapers and news magazines quite clearly show terror in the faces of, say, hostages with guns pointed at them, or the grief of families at funerals. Richard Avedon's 1956 portrait of actor Bert Lahr, in character as Estragon from the play Waiting for Godot, shows sadness. Sally Mann's 1986 photograph of two of her children visiting their grandfather at the hospital, entitled, "He is Very Sick," reveals the children's discomfort. And all of us have certainly seen many pictures of young children experiencing joy during happy occasions.

But that doesn't mean there is always emotion present. Sometimes, the extra things people see are deliberately put there after the fact by enterprising photographers or writers. The world's best-known photographic portrait is probably Yousuf Karsh's 1941 picture of Winston Churchill. It is a very well made portrait, and it is also one of the most read-into portraits.

But that doesn't mean there is always emotion present. Sometimes, the extra things people see are deliberately put there after the fact by enterprising photographers or writers. The world's best-known photographic portrait is probably Yousuf Karsh's 1941 picture of Winston Churchill. It is a very well made portrait, and it is also one of the most read-into portraits.

Caption writers, and Karsh himself, began building the legend almost before the first prints were dry. The story goes like this: Karsh set up his equipment and was ready to take the portrait, but there was just one thing wrong. Churchill was puffing on a fresh cigar. Karsh picked up an ash tray, held it in front of Churchill, and asked, "Will you please remove it, sir?" The request was ignored. Karsh went back behind the camera to check the focus one last time. He then walked back to Churchill, said, "Forgive me, sir," and pulled the cigar from the great man's mouth. "By the time I had walked the four to six feet back to my camera," Karsh writes, "he was looking as belligerently at me as if he could have devoured me. And I took the picture."

I've looked at that photograph countless times over the years, and I don't see belligerence. I simply see a lack of a smile. The belligerence claim is further called into question by the fact that Churchill smiled warmly for a second picture made a moment later. Even a man of Karsh's considerable charm couldn't have turned Churchill from lion to lamb in an instant.

One of my favorite interpretations of a photograph claims to detect much more than emotion. It says that a 1924 photograph taken by Alfred Stieglitz of his lover, the artist Georgia O'Keeffe, standing against her sister Ida, illustrates the nature of the relationships among them. In a 1993 auction catalog that included a print of this image, an unidentified writer tells what he or she sees:

Interestingly, Stieglitz represents the sisters as sharing the same body (their two heads emerging from the black mass of their coats) — an obvious reference to kinship and, perhaps to the dark (mysterious) female element. Their facial expressions and body language reveal much about the sisters, and of course, are also telling with regard to their relationship to Stieglitz: Georgia stands confidently, erectly, and confronts her paramour with the arrogant and direct gaze so familiar in many of the later studies; Ida appears softer, her mien unsure and unassuming, and averts her gaze to the left. As a pictorial study of contrasting female types the portrait is emblematic of the formalist underpinnings of Stieglitz's directorial eye, and his dual, and conflicting, perception of women.

Wow! Two years later, another observer wrote this about the photo: "Ida casts a nervous glance her sister's way as if to suggest that she knows something that her sister doesn't."

It must be remembered that photographers are working in the visual realm. It appears to me the details recorded in the Stieglitz photograph — the similar clothing, Georgia looking at the camera lens and Ida looking away — were just pieces that made things visually interesting. Stieglitz himself once said, "I want solely to make an image of what I have seen, not of what it means to me. It is only after I have created an equivalent of what has moved me that I can begin to think about its significance." That's it. The interpretations come later.

Despite the auction catalog writer's fine hyperbole, the photograph sold for $24,200, which was below the $25,000 — $35,000 preauction estimate.

Eight years after taking the photo of the sisters, Stieglitz made a photograph of his friend Dorothy Norman's hands. The actor Charlie Chaplin saw the photo at Stieglitz's New York gallery and spent the next 30 minutes staring at it. Chaplin told him, "Stieglitz, what you've gotten in that!"

"I didn't ask him what he saw," Stieglitz later recalled.

Edward Weston made a famous picture of Charis Weston during a mountain hiking trip. Had she not been fully clothed, the manner in which she was sitting would have been of considerable interest to a gynecologist. Despite the fact that the picture shows an attractive woman in a far from ladylike pose, one observer looked beyond the person to find human characteristics. Writing about the picture 50 years after it was made, Wilson said: "Then there was the critic who determined that the sexuality was symbolized by the indentations in the rock wall behind me."

OK, let me get this straight. The woman isn't sexy, the rocks are? Hey, look at those rocks — hubba, hubba?

In this essay, I have tried my best to avoid doing what I am complaining about — reading things into photographs. Just as a magician can spot a fraudulent mystic when a scientist cannot, I believe my background as someone who has photographed thousands of people makes it possible for me to objectively view the photographs discussed here.

About the author:

William McEwen's photographs have been exhibited throughout the United States, are in several public collections and have been published internationally. His book "People and Portraits: Reflections and Essays" was published this summer. More of his work can be viewed on line at http://www.flash.net/~wmcewen.

Our good friend Donald E. Simanek (rhymes with "mnemonic") and his colleague John C. Holden (rhymes with lots of words), have just published a very entertaining book, "Science Askew: A Lighthearted Look at the Scientific World." You can find out more about it at: http://www.lhup.edu/~dsimanek/humor.htm#askew and our readers who go there can use the magic discount word "GRU53TO" to get 15% off the regular price. For your investment, you will share some of the fascinating philosophy that Simanek (rhymes with "demonic") has been espousing for many long decades. The famous Konrad Finagle (rhymes with "bagel") appears through the book, which Simanek (rhymes with "tectonic") describes as "a refreshing antidote to respectable and stuffy scientific journals." We find here the details of "continental drip," a subject largely ignored by traditional science, and we are finally informed of the mathematicians who came to rule civilization during the Stochastic Era, and survived the dreadful locus plagues to make their glorious capture of the Tower of Hanoi and drive the rebellious Surds from the area. Our illustration here by John Holden, taken from the cover of the book, illustrates the enemy in full regalia and armor.

Our good friend Donald E. Simanek (rhymes with "mnemonic") and his colleague John C. Holden (rhymes with lots of words), have just published a very entertaining book, "Science Askew: A Lighthearted Look at the Scientific World." You can find out more about it at: http://www.lhup.edu/~dsimanek/humor.htm#askew and our readers who go there can use the magic discount word "GRU53TO" to get 15% off the regular price. For your investment, you will share some of the fascinating philosophy that Simanek (rhymes with "demonic") has been espousing for many long decades. The famous Konrad Finagle (rhymes with "bagel") appears through the book, which Simanek (rhymes with "tectonic") describes as "a refreshing antidote to respectable and stuffy scientific journals." We find here the details of "continental drip," a subject largely ignored by traditional science, and we are finally informed of the mathematicians who came to rule civilization during the Stochastic Era, and survived the dreadful locus plagues to make their glorious capture of the Tower of Hanoi and drive the rebellious Surds from the area. Our illustration here by John Holden, taken from the cover of the book, illustrates the enemy in full regalia and armor.

(Aside: the delightful absurdities offered here are hardly differentiated from claims made by parapsychologists, so beware.....)

Reader Dr. Greg Camp, Ph.D., is the Lewis and Clark Historian of the State Historical Society of North Dakota in Bismarck, ND. As an historian, Dr. Camp views sensational reports with a more critical eye than a TV producer or supermarket tabloid editor. He shares with us here the details of an investigation he made a few years ago.

About a week ago I was watching television when I saw an advertisement for a new paranormal events program on Fox television. The title had something to do with conspiracies, thus making it expected fare from Rupert Murdoch's stable of offerings. At any rate, one of the things they showed on the advertisement was a tabloid paper with a "staircase to hell" (with apologies, I assume, to Led Zeppelin) sidebar. This intrigued me, as nearly five years ago I was asked to look into a similar story on the lonely plains of North Dakota.

In 1998, there were websites and even newspaper accounts of a so-called "back door to hell" located in northeast North Dakota. Reports stated that there was a staircase found under a strange monument in this remote part of the state and that locals claimed to have heard the cries of the damned from time to time. Even that staunch reporter of all things logical, FATE magazine, carried a story after our investigation. FATE, however, chose not to mention any of those who actually investigated.

A newspaper reporter from the small North Dakota hamlet of Velva ran a story on this structure during the summer of 1998. He was swamped with personal accounts of what had been seen and heard over the course of the 20th century at that site. That is when he telephoned me for some help. A couple of weeks later we visited the place of this supposed occult mystery and found, obviously enough, nothing strange to write about.

Located on a farm some thirty-five miles northwest of Devils Lake, North Dakota (appropriate name, eh?), the back door to hell was nothing more than a cement vault, half buried in the soil, with Masonic markings on it. The traditional "G" with compass was engraved over the entrance, with a more cryptic symbol on the outside rear of this 14' x 8' structure. That rear symbol, borrowed from ancient Egyptian religion, I found was actually familiar to anyone with a passing knowledge of the Egyptian Book of the Dead . The vault itself was half buried in the soil and had a short series of steps down into its interior. That is the extent of the staircase to hell — some five steps or so down to simply enter it. Being a mason, the farmer who constructed it modeled it on the secret chamber under the Temple in Jerusalem of Freemasonic lore.

The vault was built in the 1890's by a Danish farmer who had strong Masonic-Rosicrucian beliefs. It was built adjacent to his home in the midst of a small grove of trees. The house had long since disappeared by the time I got there, leaving only a strange-looking vault alone on the prairie. One can understand how this became the source of local legend and myth. Today, the story persists in that part of the state. Urban legends and occult myth are difficult to smother even though their veracity can be demonstrated to be false. Sadly, ongoing conspiracy theories about the Masons in all probability fueled some of this speculation.

A sober, factual account. Fox-TV network, take note. Hello! Anyone home.....?

I note that the town of Velva, where this dreaded portal is located is just a piece down the road from Voltaire, an influence that has apparently not effected the local populace. Perhaps overpowered by vibes from Devil's Lake.....?

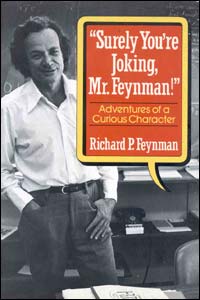

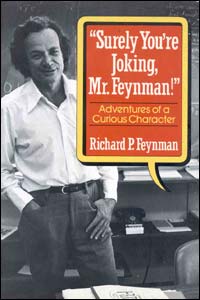

Well, at my home this week the hot water heater blew up, taking with it my cable-TV connection. A desperate situation, one that forced me to take a book in hand while preparing for my night's sleep, unshowered. Close at hand was Dick Feynman's book "Surely You're Joking, Mr. Feynman!" (Norton, 1985). In this hilarious and revealing tome I came upon his essay on "Cargo Cult Science," a piece which I'd essentially forgotten about as an excellent example of Dick's thinking process and his concern with poor science. This essay was adapted from a Caltech commencement address given by Richard in 1974, and I have edited it down for your consumption. It is very much directed to students, and serves as a warning against getting caught up in what we now know as "politically correct" attitudes at the expense of doing real science. Please, read the book. It's brilliant, which I hardly need mention, knowing the source.....

Well, at my home this week the hot water heater blew up, taking with it my cable-TV connection. A desperate situation, one that forced me to take a book in hand while preparing for my night's sleep, unshowered. Close at hand was Dick Feynman's book "Surely You're Joking, Mr. Feynman!" (Norton, 1985). In this hilarious and revealing tome I came upon his essay on "Cargo Cult Science," a piece which I'd essentially forgotten about as an excellent example of Dick's thinking process and his concern with poor science. This essay was adapted from a Caltech commencement address given by Richard in 1974, and I have edited it down for your consumption. It is very much directed to students, and serves as a warning against getting caught up in what we now know as "politically correct" attitudes at the expense of doing real science. Please, read the book. It's brilliant, which I hardly need mention, knowing the source.....

During the Middle Ages there were all kinds of crazy ideas, such as that a piece of rhinoceros horn would increase potency. Then a method was discovered for separating the ideas — which was to try one to see if it worked, and if it didn't work, to eliminate it. This method became organized, of course, into science. And it developed very well, so that we are now in the scientific age. It is such a scientific age, in fact, that we have difficulty in understanding how witch doctors could ever have existed, when nothing that they proposed ever really worked — or very little of it did.

But even today I meet lots of people who sooner or later get me into a conversation about UFOS, or astrology, or some form of mysticism, expanded consciousness, new types of awareness, ESP, and so forth. And I've concluded that it's not a scientific world.

Most people believe so many wonderful things that I decided to investigate why they did. And what has been referred to as my curiosity for investigation has landed me in a difficulty where I found so much junk that I'm overwhelmed....

He launches into an Esalen adventure in which he suppresses his erudition to learn just how naive the afficionados are, then continues....

That's just an example of the kind of things that overwhelm me. I also looked into extrasensory perception and PSI phenomena, and the latest craze there was Uri Geller, a man who is supposed to be able to bend keys by rubbing them with his finger. So I went to his hotel room, on his invitation, to see a demonstration of both mindreading and bending keys. He didn't do any mindreading that succeeded; nobody can read my mind, I guess. And my boy held a key and Geller rubbed it, and nothing happened. Then he told us it works better under water, and so you can picture all of us standing in the bathroom with the water turned on and the key under it, and him rubbing the key with his finger. Nothing happened. So I was unable to investigate that phenomenon.

The fine hand of the publishers lawyer enters here. Dick's original account of this event included the fact that Geller was very suspicious of him, and tried all sorts of misdirection, but to no avail. Then Geller suddenly marched into the bathroom with the witnesses hurrying to catch up with him, turned on the sink faucet, and inserted the end of the key up into the faucet and the stream of water before they could say a word. Dick commented that the key was now out of sight, had been out of sight since Geller turned and hurried to the bathroom with it, and declared the security to have been broken. Geller dismissed the witnesses. In conversation with me later, Dick said that he'd noticed how simple it would have been for Geller to put a bend into the key while it was firmly held in the faucet exit, and concealed by the stream of water, just by pulling it sideways and then revealing a bend. It was both Dick and Geller who aborted the "experiment" at that point.

But then I began to think, what else is there that we believe? (And I thought then about the witch doctors, and how easy it would have been to check on them by noticing that nothing really worked.)....

Here Dick Feynman looked into some of the fanciful ideas of modern educational theory and methods of handling crime, and labeled them unscientific.....

So we really ought to look into theories that don't work, and science that isn't science.

I think the educational and psychological studies I mentioned are examples of what I would like to call cargo cult science. In the South Seas there is a cargo cult of people. During the war they saw airplanes land with lots of good materials, and they want the same thing to happen now. So they've arranged to make things like runways, to put fires along the sides of the runways, to make a wooden hut for a man to sit in, with two wooden pieces on his head like headphones and bars of bamboo sticking out like antennas — he's the controller — and they wait for the airplanes to land. They're doing everything right. The form is perfect. It looks exactly the way it looked before. But it doesn't work. No airplanes land. So I call these things cargo cult science, because they follow all the apparent precepts and forms of scientific investigation, but they're missing something essential, because the planes don't land....

We've learned from experience that the truth will out. Other experimenters will repeat your experiment and find out whether you were wrong or right. Nature's phenomena will agree or they'll disagree with your theory. And, although you may gain some temporary fame and excitement, you will not gain a good reputation as a scientist if you haven't tried to be very careful in this kind of work. And it's this type of integrity, this kind of care not to fool yourself, that is missing to a large extent in much of the research in cargo cult science.

A great deal of their difficulty is, of course, the difficulty of the subject and the inapplicability of the scientific method to the subject. Nevertheless, it should be remarked that this is not the only difficulty. That's why the planes don't land — but they don't land.

We have learned a lot from experience about how to handle some of the ways we fool ourselves. One example: Millikan [a prominent American physicist, 1868-1953] measured the charge on an electron by an experiment with falling oil drops, and got an answer which we now know not to be quite right. It's a little bit off, because he had the incorrect value for the viscosity of air. It's interesting to look at the history of measurements of the charge of the electron, after Millikan. If you plot them as a function of time, you find that one is a little bigger than Millikan's, and the next one's a little bit bigger than that, and the next one's a little bit bigger than that, until finally they settle down to a number which is higher.

Why didn't they discover that the new number was higher right away? It's a thing that scientists are ashamed of — this history — because it's apparent that people did things like this: When they got a number that was too high above Millikan's, they thought something must be wrong — and they would look for and find a reason why something might be wrong. When they got a number closer to Millikan's value they didn't look so hard. And so they eliminated the numbers that were too far off, and did other things like that. We've learned those tricks nowadays, and now we don't have that kind of a disease.

But this long history of learning how to not fool ourselves — of having utter scientific integrity — is, I'm sorry to say, something that we haven't specifically included in any particular course that I know of. We just hope you've caught on by osmosis.

The first principle is that you must not fool yourself — and you are the easiest person to fool. So you have to be very careful about that. After you've not fooled yourself, it's easy not to fool other scientists. You just have to be honest in a conventional way after that.

I would like to add something that's not essential to the science, but something I kind of believe, which is that you should not fool the layman when you're talking as a scientist. I am not trying to tell you what to do about cheating on your wife, or fooling your girlfriend, or something like that, when you're not trying to be a scientist, but just trying to be an ordinary human being. We'll leave those problems up to you and your rabbi. I'm talking about a specific, extra type of integrity that is not lying, but bending over backwards to show how you're maybe wrong, that you ought to have when acting as a scientist. And this Is our responsibility as scientists, certainly to other scientists, and I think to laymen.

For example, I was a little surprised when I was talking to a friend who was going to go on the radio. He does work on cosmology and astronomy, and he wondered how he would explain what the applications of this work were. "Well," I said, "there aren't any." He said, "Yes, but then we won't get support for more research of this kind." I think that's kind of dishonest. If you're representing yourself as a scientist, then you should explain to the layman what you're doing — and if they don't want to support you under those circumstances, then that's their decision....

Feynman next discusses the 1937 work of psychologist Paul Thomas Young, who found serious discrepancies in then-current experiments involving rats solving mazes. This extensive and thorough body of work, he pointed out, has been totally ignored by psychologists, who use the tired old standards and as a result obtain spurious results.

Another example is the ESP experiments of Mr. Rhine, and other people. As various people have made criticisms — and they themselves have made criticisms of their own experiments — they improve the techniques so that the effects are smaller, and smaller, and smaller until they gradually disappear. All the parapsychologists are looking for some experiment that can be repeated — that you can do again and get the same effect — statistically, even. They run a million rats — no, it's people this time — they do a lot of things and get a certain statistical effect. Next time they try it they don't get it any more. And now you find a man saying that it is an irrelevant demand to expect a repeatable experiment. This is science?

This man also speaks about a new institution, in a talk in which he was resigning as Director of the Institute of Parapsychology. And, in telling people what to do next, he says that one of the things they have to do is be sure they only train students who have shown their ability to get PSI results to an acceptable extent — not to waste their time on those ambitious and interested students who get only chance results. It is very dangerous to have such a policy in teaching — to teach students only how to get certain results, rather than how to do an experiment with scientific integrity.

So I have just one wish for you — the good luck to be somewhere where you are free to maintain the kind of integrity I have described, and where you do not feel forced by a need to maintain your position in the organization, or financial support, or so on, to lose your integrity. May you have that freedom.

I predict, for 2002 P.E., we will see no Nobel Prize awarded to a parapsychologist, that Sylvia Browne will continue to fail answering our challenge, that Brian Josephson will not respond to the American Physical Society's acceptance of his challenge on homeopathy, that Fox-TV will run even more outrageous material, that John Edward will begin to notice that viewers are catching on to his methods, that the JREF will not award its million-dollar prize, that Dr. Gary Schwartz will still not provide us with the evidence he says he has for life-after-death, and the University of Arizona (who were offered the million-dollar prize from the JREF if that data was forthcoming) will still refuse to ask Schwartz for that data — because they're doubtful that it exists.

I predict that the Pope will create more saints, and ask for peace on Earth.

I predict that we'll get even sillier in 2002. That's the really sure item.....

Our colleague Andrew Harter, an accomplished magician in his own right, is the man who handles the truckloads of applications that continue to pour in at the JREF, regarding our million-dollar challenge. Last year, when the "Masked Magician" showed up on the Fox-TV network purporting to reveal the major secrets of the professional magician's act, Andrew and I began receiving inquiries from the media and from magicians who wanted our "take" on the situation. I simply dismissed the dismal matter as a mean-spirited, desperate reach for ratings, and predicted — correctly — that the effort would pass largely un-noticed and would be much less damaging than many of our magician friends had feared. Andrew made a deeper analysis of the situation, which I share with you here....

Our colleague Andrew Harter, an accomplished magician in his own right, is the man who handles the truckloads of applications that continue to pour in at the JREF, regarding our million-dollar challenge. Last year, when the "Masked Magician" showed up on the Fox-TV network purporting to reveal the major secrets of the professional magician's act, Andrew and I began receiving inquiries from the media and from magicians who wanted our "take" on the situation. I simply dismissed the dismal matter as a mean-spirited, desperate reach for ratings, and predicted — correctly — that the effort would pass largely un-noticed and would be much less damaging than many of our magician friends had feared. Andrew made a deeper analysis of the situation, which I share with you here....

Flipping through TV channels on New Year’s Day, I found my expectations both met and shattered. On CBS, both John Rennie of Scientific American Magazine, and Bill Nye "the Science Guy," were interviewed on the future of science and technology, and between them they gave a lucid, simplified, view of nanotechnology and other valid and fascinating aspects of what’s probably coming into our lives in the next few decades.

Flipping through TV channels on New Year’s Day, I found my expectations both met and shattered. On CBS, both John Rennie of Scientific American Magazine, and Bill Nye "the Science Guy," were interviewed on the future of science and technology, and between them they gave a lucid, simplified, view of nanotechnology and other valid and fascinating aspects of what’s probably coming into our lives in the next few decades.

But that doesn't mean there is always emotion present. Sometimes, the extra things people see are deliberately put there after the fact by enterprising photographers or writers. The world's best-known photographic portrait is probably Yousuf Karsh's 1941 picture of Winston Churchill. It is a very well made portrait, and it is also one of the most read-into portraits.

But that doesn't mean there is always emotion present. Sometimes, the extra things people see are deliberately put there after the fact by enterprising photographers or writers. The world's best-known photographic portrait is probably Yousuf Karsh's 1941 picture of Winston Churchill. It is a very well made portrait, and it is also one of the most read-into portraits.

Our good friend Donald E. Simanek (rhymes with "mnemonic") and his colleague John C. Holden (rhymes with lots of words), have just published a very entertaining book, "Science Askew: A Lighthearted Look at the Scientific World." You can find out more about it at:

Our good friend Donald E. Simanek (rhymes with "mnemonic") and his colleague John C. Holden (rhymes with lots of words), have just published a very entertaining book, "Science Askew: A Lighthearted Look at the Scientific World." You can find out more about it at:  Well, at my home this week the hot water heater blew up, taking with it my cable-TV connection. A desperate situation, one that forced me to take a book in hand while preparing for my night's sleep, unshowered. Close at hand was Dick Feynman's book "Surely You're Joking, Mr. Feynman!" (Norton, 1985). In this hilarious and revealing tome I came upon his essay on "Cargo Cult Science," a piece which I'd essentially forgotten about as an excellent example of Dick's thinking process and his concern with poor science. This essay was adapted from a Caltech commencement address given by Richard in 1974, and I have edited it down for your consumption. It is very much directed to students, and serves as a warning against getting caught up in what we now know as "politically correct" attitudes at the expense of doing real science. Please, read the book. It's brilliant, which I hardly need mention, knowing the source.....

Well, at my home this week the hot water heater blew up, taking with it my cable-TV connection. A desperate situation, one that forced me to take a book in hand while preparing for my night's sleep, unshowered. Close at hand was Dick Feynman's book "Surely You're Joking, Mr. Feynman!" (Norton, 1985). In this hilarious and revealing tome I came upon his essay on "Cargo Cult Science," a piece which I'd essentially forgotten about as an excellent example of Dick's thinking process and his concern with poor science. This essay was adapted from a Caltech commencement address given by Richard in 1974, and I have edited it down for your consumption. It is very much directed to students, and serves as a warning against getting caught up in what we now know as "politically correct" attitudes at the expense of doing real science. Please, read the book. It's brilliant, which I hardly need mention, knowing the source.....