PART ONE. HOW IT LOOKED AND WHAT IT DID

I hold in my hand a small booklet published in London titled, A SELECTION OF FIFTY GAMES, FROM THOSE PLAYED BY THE AUTOMATON CHESS- PLAYER DURING ITS EXHIBITION IN LONDON, IN 1820. This booklet was sold at the site of a popular exhibition that featured a remarkable automaton, one that played chess with great skill. Very highly-ranked players of the day were regularly -- though not always -- defeated by this mechanical wonder, much to the delight of the viewing public. The exhibitor, one Monsieur Maelzel, was hard-pressed to accommodate the 300 persons who each day gladly paid the five shillings admission apiece to see this marvel at work. Maelzel was eventually to take this marvel off to America and discover that the former colonists there were just as ready to be taken in by his hoax as were the citizens of Europe and England.

For it was a hoax. This will not surprise anyone familiar with the complexity of the game of chess, or anyone aware of the existence of IBM's Big Blue, the real electronic wonder that has demonstrated its superiority over human chess masters only in recent years, though only at the expenditure of a small fortune and the use of enormous talent, technology, and dedication by a formidable team of engineers. In 1820, a chess-playing automaton was simply not possible.

I mention the small book because I am titillated by the situation of the real chess-master behind the scenes, the human being who was cleverly concealed within the apparatus, grinding his teeth at the fact that in the book, credit for the chess- playing was being naively ascribed to the mass of cogs and wheels within the device, rather than to him. The man who held that strange position was Mouret (chess afficionados at this period usually referred to players by family names only, an affection that robs us of a means of further identifying these persons) who held the position for only a year, then stayed behind in England to lose his mind to brandy. There were actually some fifteen eminent chess players who, over the 85 years that this marvel was in existence, occupied the cramped innards of the machine.

What most interests me about the whole story of the "automaton" is that even very skilled, clever, investigators were taken in by it. Those who never actually witnessed it in action were quite prevented from forming any proper opinion of it, since they were forced to depend upon the descriptions of others who provided -- often very innocently -- quite hyperbolic and inaccurate descriptions of what they had witnessed.

One of the most fervent supporters of the reality of the Automaton's mechanical nature was Charles Gottlieb Windisch, a German who studied the device as early as 1769, when it was first unveiled by its Hungarian inventor, Wolfgang de Kempelen. This clever inventor had mentioned to his queen, Empress Maria Theresa, who was a chess afficionado, that he felt he could construct a mechanism that would actually play a game of chess, and when the Empress became enthusiastic over the notion, he set to work to produce it for her edification. Less that a year later, he appeared at court to demonstrate the successful device he had put together. (Being of a naturally suspicious nature, dear reader, I have a nagging hunch that perhaps -- just perhaps -- Kempelen already had the thing under construction, and encouraged Her Majesty to demand that it be designed, constructed, and presented for her inspection. The time-frame for the construction of such a machine was just too small to be real.) Windisch gave detailed descriptions of how the exhibitor would demonstrate that there was no possibility of a human being concealed within the rather large chest upon which was perched a figure that actually reached down and seized a chess piece and moved it into position as required. Where Windisch failed, however, was in certain aspects of his description. He described his experience in much the same way that a layman recounts his attendance at a magic show, missing certain important details, being misdirected away from the actual procedures, and not seeing simple items that appeared to be unimportant. To explain why this is so important to this discussion, I will give my reader an example from my own experience.

Many years back, I appeared on the NBC-TV Today Show doing a "survival" stunt in which I was sealed into a metal coffin in a swimming pool in an admitted and since-regretted attempt to out-do Harry Houdini, who had performed the stunt at the same location back in 1926. Yes, I beat his time, but I was much younger than he had been when he performed it. I had listened to an agent who assured me that this was the way to go. I have been ever since trying to forget my disrespect for Houdini. But this digression is not pertinent to the main story here.

A week following that TV show, I was standing out on Fifth Avenue in a pouring rain, supervising through a window the arrangement of a display of handcuffs and other paraphernalia that I'd loaned to a bank for an eye-catching advertisement. My raincoat collar was up about my ears, and I could thus not be easily recognized. I was astonished when an NBC director, Paul Cunningham, who had been in charge of my swimming-pool appearance, happened by. We were adjacent to the NBC studios, and he had been on his way to work. Not noticing me, but seeing my name on the bank- window display, he began excitedly describing to his companion how I had been handcuffed, wrapped in a strait-jacket, and sealed into the coffin before being submerged, on his show. "And he was free and at the surface within minutes!" he exclaimed.

With a certain small show of drama, I identified myself. Paul was ecstatic, and invited me to join them for coffee. There, while we warmed ourselves over java, I explained to him that he had unwittingly provided his listener with a description that was not only untrue, but impossible. I told him that no handcuffs nor straitjacket had been involved at all in that event, and that he was mixing up his memories of previous shows with the one he had directed. In addition, I pointed out, it is impossible to place a straitjacket on a person who is handcuffed; this is a topological paradox. In addition, I'd not made an escape from the coffin, nor had that been the stunt: I was merely surviving on a limited amount of air, and I was able to climb from the coffin when it was brought to the surface. Cunningham's version was dramatic, but simply very wrong.

We retired to an NBC studio to view a kinescope of the program in question, since Mr. Cunningham was quite sure that his version was correct, and I admit that I was a bit embarrassed to see his discomfiture as he then saw just how wrong he had been. So it is with many accounts of unusual events, since the viewer tends to incorporate errors and other details from similar events as part of his firm memory of what he believes took place. Magicians, in particular, are very familiar with this phenomenon.

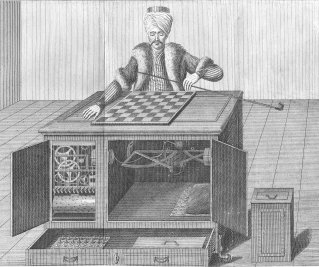

I recount this event in order to give of clearer picture of how Windisch could have erred so greatly in his description of the Chess Automaton. Obviously, it occurred to observers that there could possibly be a player concealed within the chest. To prove the contrary, the operator of course had to open all the doors and show that the inside areas of the chest were either empty or filled with equipment. That is what apparently happened. Please examine the illustration immediately above, taken from the French edition of his book, 1783. The author says at one point in his rather lengthy and detailed move-by-move account that he provided (my translation) "But don't imagine, as so many have, that the inventor closes one of the doors at the moment he opens the other; one sees all at the same time the Automaton uncovered, having the garments turned up, and the drawer opened, as well as all the doors of the chest. It is in this state that he [Kempelen] rolls it from place to place, and in which he offers it to the inspection of the curious." Note: the word "doors" was mistranslated from French as "drawers" in one English version, and then that error was copied into several other accounts. I took my version straight from the French text. There was only one drawer, the one shown at the bottom front of the figure.

Though, as already said, it had been immediately suspected by most of the public and particularly by the chess players, that a person concealed within the mechanism was actually playing the game, it was very difficult for anyone who saw the setup and the performance in person to imagine how that could be, for Kempelen was an ingenious engineer, capable of constructing a most confounding illusion and choreographing the "moves" necessary to deceive the observers. He was an experienced inventor, with a steam lift, a system for writing designed for blind persons, and several fountain mechanisms to his credit.

The illustration above is an impossible one, if it purports to show the Automaton in operating condition. The drawer at the bottom is open, as are the doors at the front. In fact the center door is missing altogether! The device was never shown in this condition while prepared to play the game; that would have been impossible without revealing the secret. It is because of such carelessness that it was difficult for the public of the time to form an informed opinion on how the trick might have been done.

Luckily, there exists a detailed description of the sequence through which Kempelen went before every performance. It was written by none other than Edgar Allan Poe, who as a detective-story teller, and because he was a frequent witness to the performance of the Automaton, was able to give details that fit exactly with the deceptive methodology that a magician would suppose for the presentation and mechanism. In fact, the various discrepancies and odd sequences used, are unexplainable by any other scenario than the one that calls for a person to be in the box.

All doors were locked, at the beginning of the demonstration. The operator would begin by pulling out the large front bottom drawer, then unlocking and opening the front door of the left-hand compartment. Inside would be seen a mass of cogs and wheels, but the viewers could only see to a certain depth toward the back, apparently because of the density of the mechanism. That door was left wide open while the operator went around the back and opened another door directly behind the already- open front door. A lit candle was then moved to and fro at that aperture and could be discerned in flashes through the mass of machinery. At that stage of the procedure, it was evident that no one could be concealed in that volume, at least. The back door was then closed and locked. Coming around the front again, the operator would next slide out the drawer fully. He would then open both the center and the right-hand front doors and display thereby the entire inside area of those two compartments. Leaving those front doors -- all three -- open, he would go around the back and open the back doors of the right-hand and center compartments. Now all three front doors and two of the back doors were open, as well as the large front drawer! And, the device was turned completely around to show all sides! You may have a difficult time imagining where the concealed chess-player could be at this point, right?

And now, dear reader, in the true spirit of Edgar Allan Poe, we will break away from our denouement of the Marvelous Chess Automaton, to continue next week, when we will provide you with the solution and reveal the eventual fates of the operators and of the machine itself.

END OF PART ONE