I’ve been a skeptic for almost as long as I can remember. There’s a story I’ve often told about being at the World’s Fair in New York City when I was eleven years old – I had already been doing magic for several years – and figuring out that the IBM pavilion had scammed me out of two weeks of allowance money with a phony computerized handwriting analysis. Although I didn’t know it at the time, when I look back I can see that as a defining moment of sorts. A moment when my already consuming interest in magic crossed circuits with my fascination with science, and with my admiration for Harry Houdini’s historic work as a psychic-buster, and crystallized my identity as a skeptic. But of course, not quite yet as an activist, movement-oriented skeptic. That would take longer. But I think it’s safe to say that by age eleven I was already personally, as an individual, a skeptic.

World’s Fair in New York City when I was eleven years old – I had already been doing magic for several years – and figuring out that the IBM pavilion had scammed me out of two weeks of allowance money with a phony computerized handwriting analysis. Although I didn’t know it at the time, when I look back I can see that as a defining moment of sorts. A moment when my already consuming interest in magic crossed circuits with my fascination with science, and with my admiration for Harry Houdini’s historic work as a psychic-buster, and crystallized my identity as a skeptic. But of course, not quite yet as an activist, movement-oriented skeptic. That would take longer. But I think it’s safe to say that by age eleven I was already personally, as an individual, a skeptic.

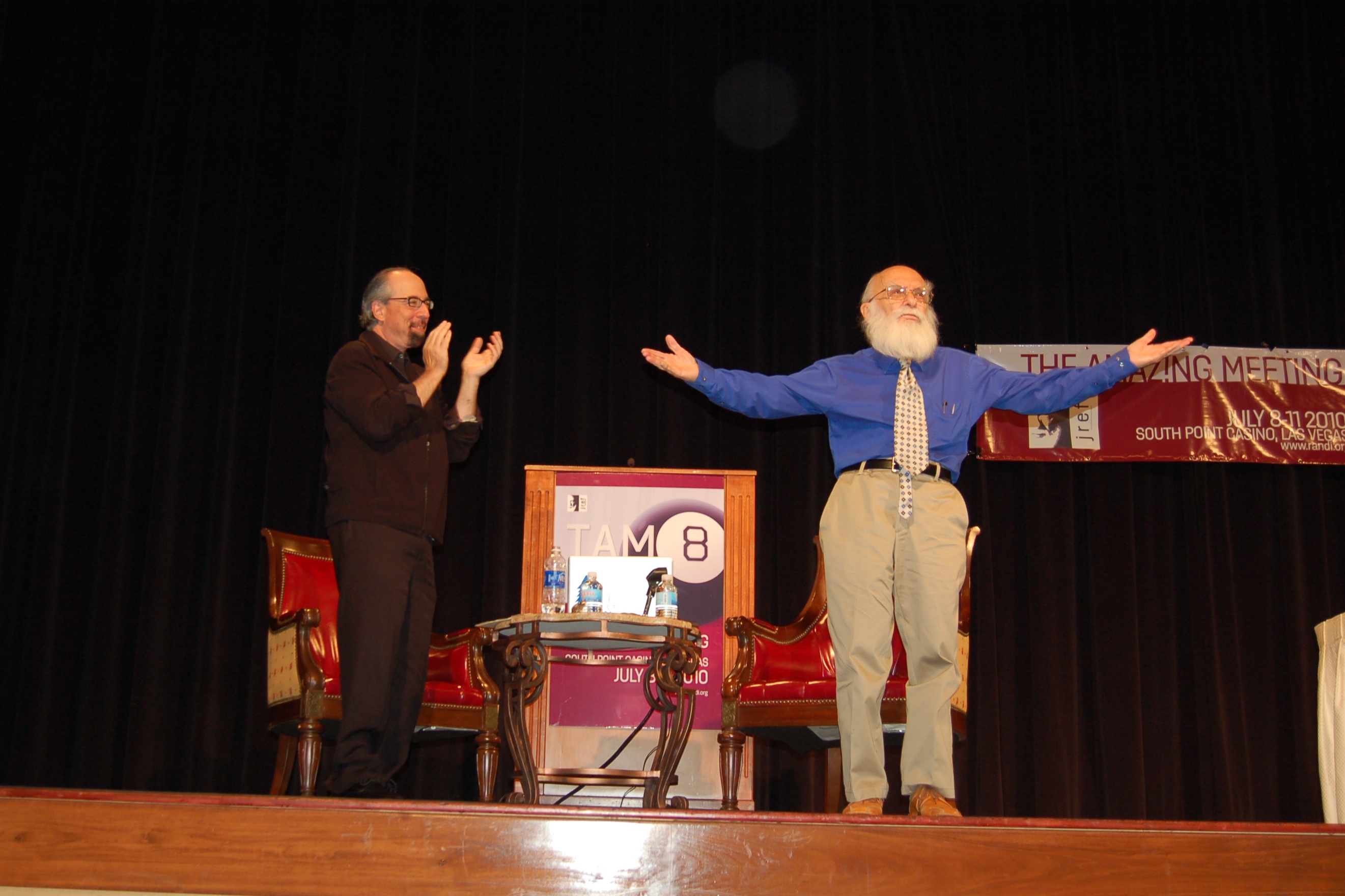

I can still recall watching The Amazing Randi on television when I was a little boy, on a popular local New York Sunday children’s show called “Wonderama,” hosted by Sonny Fox (who spoke at TAM a few years ago and with whom I was thrilled to get a photo!). But I was in my early twenties when Randi wrote a book called The Magic of Uri Geller that would change my life. (I still prefer that original title to the later reissue as The Truth About Uri Geller. One word tells the whole story: MAGIC. As in TRICKS. So simple and direct and devastatingly blunt. So … Randi.)

Randi’s book didn’t tell me anything I didn’t already know about Uri Geller in particular or psychics in general. I’d been weaned on Harry Houdini along with the art and craft and psychology of deception. But that book radicalized me about the harm that con men and phony psychics do, whether it is distracting the pursuit of science down rabbit holes of confusion and anti-science, or setting the public up with toxic misinformation that can readily lead to victimization by an army of similar con men and women and their catalog of techniques with which to take people’s time, and money, and sometimes even lives away from them.

I would go into major bookstores that didn’t yet carry Randi’s Geller book, have them order it to get it onto their shelves, and buy six copies and give them away. Then when they were gone, I’d go to another store and get them to order it. And so on.

That book instilled in me what DJ Grothe refers to as the righteous indignation that fuels so many of us involved in the work of skepticism. And there I was, set on the path that has connected magicians with the cause of critical thinking and rationality for centuries.

Indeed, there is a long and honorable history and tradition of magicians being “honest liars.” (That’s my website, by the way: honestliar.com. And it’s been my moniker for more than 25 years, a concept inspired by Randi, and now the title of a new documentary about his life and work.) More than four centuries ago, in 1584, a barrister by the name of Reginald Scot wrote what is now considered to be a classic Elizabethan text entitled The Discoverie of Witchcraft. It was a book of rational inquiry and skepticism – specifically, skepticism about charges of witchcraft in the era of Jamesian England. Scot wasn’t quite ready to yet say that witches didn’t exist, but he questioned the evidence being presented for those claims – and pronounced himself highly skeptical of that evidence. A true skeptic. (And a fine example of how a believer of sorts can also be a skeptic – even a groundbreaking one.)

As part of his argument about how easily people can be deceived, Scot included a small chapter of magic tricks. He probably had an interest in magic himself, but he certainly used the assistance of a French magician who was working in London at the time to help him write the chapter. And magicians still draw today on some of the tricks and principles described in that book. But the point is this: The relationship between magicians and critical thinking and skepticism goes back a very long way.

It came to a quite visible public head 300 years later in the late 19th century, in the heyday of Spiritualism and spirit séances, when many magicians, both in the United States and England, and exemplified by Harry Houdini, became prominent and controversial figures in the public eye for exposing the methods of fraudulent mediums. By the time of Houdini’s death in 1926, the use of physical phenomena – ghostly apparitions, spirits writing on slates, and the like – had essentially come to a crashing end. When you try to offer physical evidence of the supernatural, you tend to get caught. A lot.

By the time of his death, Houdini was no longer just famous as the world’s greatest escape artist; he had also become the world’s leading paranormal investigator. Some years ago at TAM, John Rennie, the then Editor-in-Chief of Scientific American magazine, recounted – with some apparent pride, I might add – the historic relationship between that magazine, Harry Houdini, and the birth of parapsychology as an alleged science. It was Houdini who first offered a personal cash prize for anyone who could demonstrate a paranormal claim under test conditions – a tradition later continued by James Randi, and today by the JREF, under Randi’s continuing guidance, and with the help of myself and, among others, Banachek, JREF board member Chip Denman, and JREF President DJ Grothe – all of us, I might add, with a shared background in magic. (Grace Denman is the non-magician on the JREF’s Million Dollar Challenge committee.)

Then, fifty years after Houdini’s death – and the concurrent death of Spiritualism – out of the Middle East came a new flavor of extraordinary claimant, a psychic who would offer renewed physical evidence in the name of paranormal abilities, supposedly endowed by beings from another planet, who had gifted him with the power to bend silverware and keys with the power of his mind.

And once more a magician stepped forward to battle that dragon, protecting himself with the armor of an expertise in deception, and attacking with the sword of rationalism. Houdini had insisted that parapsychologists, faced with the likelihood of cheating among their experimental subjects, risked being made fools of and worse if they did not seek the assistance of experts in deception – namely magicians.

In the 1970s, Randi offered the same message – and not only did scientists and parapsychologists ignore those warnings at their peril, but Randi offered graphic demonstration of the principles at work with the now infamous Project Alpha, which also birthed the skeptical and mentalist career of a young man named Steve Shaw, now better known to the world as Banachek.

And sure enough, this thread of magic and skepticism would continue to bore right into the birth of the modern skeptical movement, with the creation, in 1976, of CSICOP: The Committee for the Scientific Investigation of Claims of the Paranormal. The founding members of CSICOP included scientists, academics, and science writers, along with James Randi, Ray Hyman, James Alcock, and Martin Gardner – who possessed strong personal and professional experience and expertise in magic. (A skill set also shared by a later notable addition to CSICOP, the investigator and magician Joe Nickell.)

So Randi, through the pages of his book, radicalized me, serving as the catalyst that would eventually transform me from personal skeptic to skeptical activist. And over the ensuing years I became a regular reader of Skeptical Inquirer, and kept up as a supporter of CSICOP and the goals of the skeptical movement. But it wasn’t until I met Chip and Grace Denman in Washington DC, in 1985, that I began to take the next steps toward becoming a bona fide activist and committed public skeptic. We met and quickly discovered that we were all long-time fans of Randi and CSICOP, and shared our mutual surprise and frustration that there was no skeptic group in the Washington DC area – and that if anyplace in the world could use a little rationality, it was the nation’s capital. Two years later we were still waiting for someone to do something about it, until we finally realized that it probably would have to be us.

So twenty-six years ago we started the National Capital Area Skeptics in the Washington DC area, with the help of the late Phil Klass, one of CSICOP’s greatest warrior rationalists. A mere two years later, NCAS hosted a tremendously successful national CSICOP conference, and Randi and the Denmans and I have been thoroughly intertwined ever since.

Twenty years later, in 2007, I helped organize the New York City Skeptics. Two years after that, NYCS joined with the New England Skeptical Society and the Skeptics Guide to the Universe folks to create NECSS, the Northeast Conference on Science and Skepticism, and this coming April I will serve as on-stage host for the fifth of those successful regional gatherings, which has now expanded to a program of two full days plus ancillary events.

I’ve been a close ally of Randi’s since before there ever was a James Randi Educational Foundation. And while I’ve been an unofficial friend and advisor of sorts to the JREF since its inception, I currently serve as chairman of the Advisory Committee to the President, and as a member of the Million Dollar Challenge committee. And concurrent with this blog post – not my first by any means, but one that occurs in a significant new context – I am honored and privileged to have now been made a Senior Fellow of the foundation. Stay tuned to this space. There is much, much more to come.

Jamy Ian Swiss is Senior Fellow at the JREF. He blogs regularly at randi.org.