The following is a contribution to the JREF’s ongoing blog series on skepticism and education. If you are an educator and would like to contribute to this series, please contact This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it..

During TAM 2012, I was in the audience for Tim Farley’s workshop on online skeptical activism, and in what turned out to be a departure from the program, Tim introduced Shane Greenup, the developer of the “rbutr” browser extension. Rbutr, like the invaluable Web of Trust, adds another layer of information to the Internet, one of crowd-sourced commentary, evaluations, and reviews. I have been using it extensively in the last few weeks as I have pursued a project regarding the notorious cancer doctor Stanislaw Burzynski. As you may remember, a Burzynski supporter named Marc Stephens made headlines about a year ago when he sent quasi-legalistic threatening letters to skeptics who have raised questions about Burzynski’s unproven “antineoplaston” treatment. Burzynski’s shill crossed a frightening line, however, when he sent teenaged blogger Rhys Morgan images of his home, sending the clear message, “I know where you live.”

It seems that most people learn about Burzynski through a “documentary” produced by ad man Eric Merola, called Burzynski. If you camp out on the #burzynski hashtag on twitter, most tweets about the doctor mention or recommend the movie, often including a link. His supporters (and the curious) rave about how compelling the movie is. Whenever a link has appeared, I have used rbutr to link that movie file (on YouTube, vimeo, etc.) to a damning review by David Gorski, which now lives as a bookmark in my browser menu bar. After a few weeks on the hashtag, I have found that I have already tagged most of the versions of the movie that get shared, immediately and irrevocably connecting Gorski’s analysis to the movie for anyone who has the plug-in.

Rbutr is a fairly straightforward little jobbie. When you navigate to a page, say, the Burzynski Clinic’s homepage, if a user has contributed a rebuttal, a small popup window appears at the top of the page:

As you can see, the Burzynski page has been linked to 5 rebuttals. Clicking on the rbutr button brings up a list of rebuttals already submitted.

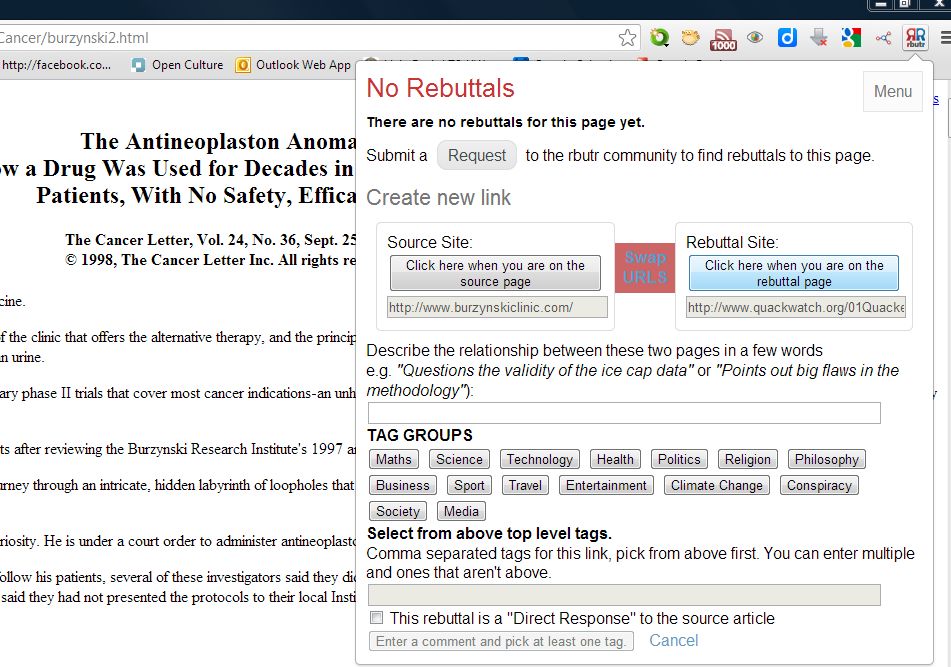

To contribute an additional rebuttal to the Burzynski Clinic page, scroll down to “submit a rebuttal” and select “this page is a source.” You will receive a message to go to the page of the rebuttal you intend to link the page to. In this case, I am going to link to a reprint of a report that was published in The Cancer Letter. When you are on the rebuttal page, click on the plugin again. You will see that the Burzynski Clinic page is already entered as the “source” page.

Click on the “Rebuttal Site” button, and the link will appear. Enter in a description of the rebuttal (“This article from The Cancer Letter includes a report by 3 independent, uncompensated researchers who visited the Clinic and found stunning inadequacies in Burzynski's trial design.”), the appropriate tags (“health, cancer, alternative medicine”), decide if your contribution is a direct rebuttal or not (in this case, the article is a general rebuttal), and submit. You have just added the sixth rebuttal to the claims of Burzynski’s site. Whenever a rbutr user goes to Burzynski’s site for information about him, they will see numerous rebuttals of his major claims to efficacy. Heck, if you were so inclined, you could link his homepage to the ongoing review of his medical license by the Texas Medical Board. Just saying.

When I heard of rbutr at TAM, my first thought was that I could use it as a teaching tool for students in my research, writing, and critical thinking classes, which often take extraordinary claims as their topic. I know that Greenup is looking for ways to get educators to use rbutr, and teaching the reading, source evaluation, and analysis skills that go into identifying a relevant and useful rebuttal is an important part of most first-year writing programs. After working with rbutr for the last several weeks, I remain convinced that it could be used to teach good research skills, and I would like to put forward a couple of recommendations for future incarnations of the plug-in that might make it more useful for education.

The first thing that developers need to be aware of (for U.S. students, at least) is FERPA, the Family Educational Rights and Protection Act, laws that outline educational institutions’ obligations to protect student data. They are pretty stringent; I can’t even release my students’ grades to their parents. So the first thing that a useful educational plug-in will do is eliminate all public personal identifiers from student work that ends up in the rbutr database. A good way to do this would be to assign student users a randomized username. I know from past experience with student blogs that changing all of your students’ usernames complicates monitoring and grading online assignments, so these usernames and contributions need to be linked to the students’ actual names behind some sort of password protection for teachers (and students) to access.

An “education edition” of rbutr would also have to take a novel approach to the “rbutr community.” Currently, when a rbutr user lands on a page with questionable content, they can request other users to research into the claims. In most of the rbutr project that I would think of assigning, this is a “do my homework for me” button. Nonetheless, the rbutr community requests page is a great place for instructors to browse for material for students to research--they are, after all, research requests. I can imagine instructors either drawing up assignments from specific requests or having students take a crack at reducing the list.

Some ethical issues need to be addressed as well. Should instructors who have a personal interest in skepticism be forcing their students to do skeptical work? I think not, however, I think that the principle of second effect is at play here. Teaching critical thinking skills needs to be at the center of all projects; any instructor who sways from that core outcome risks betraying her students’ trust in her to put their education first. For this reason, an educational version of rbutr, or of any other add-on, needs to somehow augment the learning that is going on in the classroom. For instance, on the rebuttal submission page, I would like to see a series of questions that encourage students to analyze various rhetorical features of the web page’s content: “What is the principal claim of this website?” “What type of evidence does the author supply to support this claim?” “Identify particular pieces of evidence the author presents.” “Is this the right type of evidence to support the claim?” “What assumptions need to be true for the evidence to support the claim (that is, what is the warrant?)” These types of questions are the ones we are trying to get students to ask when they examine any controversy. These questions might not build up the database directly, but the rebuttals that students find in the course of their studies would. A design that allowed instructors to ask specific questions about content and credibility would enhance the educational value of the program immensely.

Another objection that springs to mind is whether or not the model of rbutr is too much like that of turnitin.com, the online anti-plagiarization service. Many of my fellow writing teachers take strong exception to the notion that student work is being used to build up a resource that a company charges users to access, as does turnitin.com. But rbutr is not designed with the profit motive in mind, only on the enhanc/ement of knowledge. I would compare the rbutr model to that of CosmoQuest. In much the way that science teachers can assign students to work on large-scale research projects, say, marking craters on the moon for use by researchers, writing teachers can encourage students to mark lousy arguments on the Internet. Furthermore, students tend to not like what they suspect is mere busywork. Providing them a forum where they can build something of future use to others can be a strong motivator for producing good work, and rbutr has the potential to be that motivator.

Bob Blaskiewicz is a Visiting Assistant Professor at the University of Wisconsin, Eau Claire, where he teaches writing. He is co-editor of the site SkepticalHumanities.com, writes “The Conspiracy Guy” column on the CSI website, and is a panelist on the new skeptical panel show, the Virtual Skeptics, which records a live show every Wednesday night at 8:00PM Eastern.