In the science-based community, critical thinking is paramount. While we have many ideas of what critical thinking (or the lack thereof) may look like on its face, I think that it would be valuable to introduce another way of thinking about thinking.

As the newest JREF research fellow, I suppose that it is time to share with you what my research is actually about. My field of research at the moment is communication and the theories of cognitive psychology held within. Considering critical thinking as a cognitive mode that deals with evidence and analytical evaluation, the Heuristic-Systematic Model developed by communications researcher Shelly Chaiken (1980) gives a dual-process view of human information processing.

The foundation of this widely used model is rather simple: people are cognitively economical. Every attempt to seek information from a source and then process that information is governed by this rule. For example, suppose you read a press release about a new scientific finding and want to check out the study for yourself. Once you get your hands on the study, you quickly find that the paper is highly technical and laden with jargon. The amount of cognitive effort that is needed to do a simple fact check may be so high that you abandon the endeavor altogether. In short, the amount of effort that a person is willing to expend finding and processing information determines what style of thinking they will enter into.

This cognitive economy separates our thinking (or so the model predicts) into two styles: heuristic and systematic. Heuristic thinking is what could be thought of as the gut reaction style of thought. It is quick, relies on information that is already known to us (from personal experience, observation, inference, etc.), and enables us to make snap judgments on information. For example, if you view NASA as a reputable source of information, seeing a NASA logo on a press release may lead you to take the information within at face value, whether or not it is factually accurate. Heuristic thinking (given that the cognitive economy is right) relies heavily on cues to inform it. Heuristic cues can be anything that signals an acceptably quick jump in reasoning. A PhD after an author’s name, the appearance of scientific references at the bottom of an article, and even the familiarity with the information source can all lead to quick judgments that the information is credible and can be processed superficially. On the other hand, negative heuristic cues, like a frequent combination of the terms “quantum” and “consciousness,” may lead us to swiftly dismiss or ignore the information source.

Conversely, systematic thinking is a much more in-depth style, and would typify what we consider to be critical thinking. A systematic approach to seeking and processing information means looking beyond any cues like the prestige of an author and evaluating the actual message content and evidence for any claims. For example, if we actually did go through all of the references in a scientific paper and processed the information based on all this evidence that would be a systematic style of thinking.

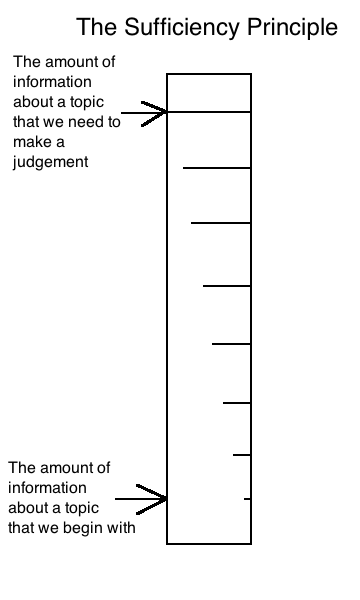

However, both ways of thinking are wrapped up in another part of the model called the sufficiency principle. Typically when we seek information about a topic we have a gap in our knowledge about that topic and need to fill that gap in order to make a confident decision about it (whether or not a claim is true, etc.). The sufficiency principle says that there is a level of information sufficiency that we must reach before we are confident; once we are there we can stop looking for and processing information. This is where the important distinction between each style of thinking comes in: the larger the gap between how much you know and how much you need to know plays a large role in determining what kind of processing you will engage in. That is to say, when looking for information and you perceive that you need to do a lot of work to get confident about that information, systematic processing is more likely because closing the gap (checking evidence, reflecting on message content, etc.) would involve a lot of cognitive effort. Conversely, if you perceive that there is only a small gap between what you already know about a topic and what you need to know, you are likely to heuristically process any information you find. Complicating things further, the way you close that gap, no matter the size, also depends on how much effort you are willing to put to the task.

when we seek information about a topic we have a gap in our knowledge about that topic and need to fill that gap in order to make a confident decision about it (whether or not a claim is true, etc.). The sufficiency principle says that there is a level of information sufficiency that we must reach before we are confident; once we are there we can stop looking for and processing information. This is where the important distinction between each style of thinking comes in: the larger the gap between how much you know and how much you need to know plays a large role in determining what kind of processing you will engage in. That is to say, when looking for information and you perceive that you need to do a lot of work to get confident about that information, systematic processing is more likely because closing the gap (checking evidence, reflecting on message content, etc.) would involve a lot of cognitive effort. Conversely, if you perceive that there is only a small gap between what you already know about a topic and what you need to know, you are likely to heuristically process any information you find. Complicating things further, the way you close that gap, no matter the size, also depends on how much effort you are willing to put to the task.

Information gaps aren’t the only things that drive you into or out of one type of thinking or another. Different motivations, capacities for information, and sources of information all play into whether or not you are going to think critically. How these come into play and even how they can bias or distort the information that you process will be dealt with in Part 2.

Now that you are at least familiar with what this model tells us about our thinking styles, what does this mean for critical thinking? For starters, heuristic thinking isn’t necessarily a bad thing. Heuristics can be harnessed to help sort through a lot of information very quickly, especially on the Internet. That being said, most heuristics can also be pitfalls for critical thought. Basing the accuracy of information on the reputation of the source can help sort through the clutter, but it can also lure you into credulity. For the reality-based community, I can offer up a few basic heuristics that are outlined in the communication literature. These are specifically heuristics that are used in an online context:

1. The Reputation Heuristic: This heuristic calls upon reputation or name recognition of websites or web-based sources as a credibility cue, rather than the close inspection of source credentials or site content (Metzger et al., 2010). This heuristic may in fact be a subset of the authority heuristic, which hinges on whether or not the website is an official authority, which is one of the most robust determinants for website credibility (Sundar, 2008).

2. The Endorsement Heuristic: This can also be identified as a “conferred credibility” (Flanagin & Metzger, 2008), meaning that people are inclined to perceive information and sources as credible if others do, without significant scrutiny. This has also been called the bandwagon heuristic.

3. The Consistency Heuristic: This states that many people indicate that they check multiple websites or sources to make sure that the information that they have sought is consistent across the Internet (Metzger et al., 2010). The more places that a piece of information appears the more credible it becomes. Although this may appear to be more systematic in nature, in that it requires more cognitive effort than most other heuristics, it is still not systematic processing because each source that adds to the preponderance of evidence is not checked thoroughly.

4. The Expectation Violation Heuristic. This heuristic states that if a website or Internet source fails to meet the expectations that accompany a particular type of site (in terms of layout, features, functionality, etc.) or message content, then the site would be judged as not credible (Metzger et al., 2010).

5. The Persuasive Intent Heuristic: This states that people tend to view online commercial information as less credible overall (Flanagin & Metzger, 2000) and that people respond negatively and almost instantaneously in regard to credibility when presented with unexpected commercial material.

Do you notice ever using some of these? Whether or not they help you or need to be corrected is something that everyone has to sort out on their own, but recognition is the first step. For the critical thinker, the important part is evaluating message content and the evidence for any claims within. Furthermore, I contend that developing a set of skeptical heuristics specifically for the web is exactly how we should teach people to find reliable Internet information (don’t trust a website that is trying to sell you something, be careful getting information from a website that makes a claim with which every other site disagrees, etc.).

Information processing in this way is immensely important to understand, especially when the goal is to increase science literacy, critical thinking skills, and to eliminate the appeals of cognitively lazy pseudoscience. Why doesn't a creationist understand the weight of evidence behind evolution? Why are 9/11 Truthers so closed off from other sources of information? How do we decrease the effort it would take for the lay audience to better process scientific information? All of these questions fall into the realm of information processing and are critical to better grasping effective communication and the skeptical mind.

REFERENCES:

Chaiken, S. (1980). The heuristic model of persuasion. In M. Zanna, J. Olsen, & C.

Herman (Eds.), Social influence: The Ontario symposium (Vol. 5, pp. 3-39). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Flanagin, A., & Metzger, M. J. (2008). Digital media and youth: Unparalleled opportunity and unprecedented reponsibility. In M. J. Metzger, & A. J. Flanagin (Eds.), Digital media, youth, and credbility (pp. 5-27). Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Metzger, M. J., Flanagin, A. J., & Medders, R. B. (2010). Social and heuristic approaches to credibility evaluation online. Journal of Communication, 60 (3), 413–439.

Sundar, S. (2008). The MAIN model: A heuristic approach to understanding technology effects on credibility. In M. Metzger, & A. Flanagin (Eds.), Digital media, youth, and credibility (pp. 73-100). Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Kyle Hill is the newly appointed JREF research fellow specializing in communication research and human information processing. He writes daily at the Science-Based Life blog and you can follow him on Twitter here.