Skepticamp Chicago 2012 was my first skepticamp although in 2011, the JREF sponsored several of these events . For those of you unfamiliar, a skepticamp is basically a social event for skeptics where everyone is more or less involved in helping it come together. If you’re not speaking then you’re helping people register or setting up equipment. A skepticamp can involve anything from lectures by leading academics to beer-fueled trivia challenges (which are especially fun when you win yourself a copy of Phil Plait’s Death From the Skies as I did). However, at its heart, it is about science-based individuals coming together to hear ideas, socialize with friends, have discussions, and hopefully to take something away from it. Events like these are the foundation upon which the skeptical movement is built, and they are a lot of fun.

. For those of you unfamiliar, a skepticamp is basically a social event for skeptics where everyone is more or less involved in helping it come together. If you’re not speaking then you’re helping people register or setting up equipment. A skepticamp can involve anything from lectures by leading academics to beer-fueled trivia challenges (which are especially fun when you win yourself a copy of Phil Plait’s Death From the Skies as I did). However, at its heart, it is about science-based individuals coming together to hear ideas, socialize with friends, have discussions, and hopefully to take something away from it. Events like these are the foundation upon which the skeptical movement is built, and they are a lot of fun.

Skepticamp Chicago was an all-day event at a mid-sized bar near downtown Chicago that by the end hosted nearly 100 people. Throughout the day 13 different talks were given on topics ranging from misconceptions about stem cells to new ideas about canine aggression to discussions of “Poe’s Law” to the search for alien extremophiles. Adding to the event, free t-shirts, stickers, and temporary tattoos were certainly a nice touch. We even had a Skype call with a skepticamp happening simultaneously in Madrid, Spain. Seeing just as many skeptics crammed into a bar on another continent gave a sense of solidarity that is sometimes lacking in the community.

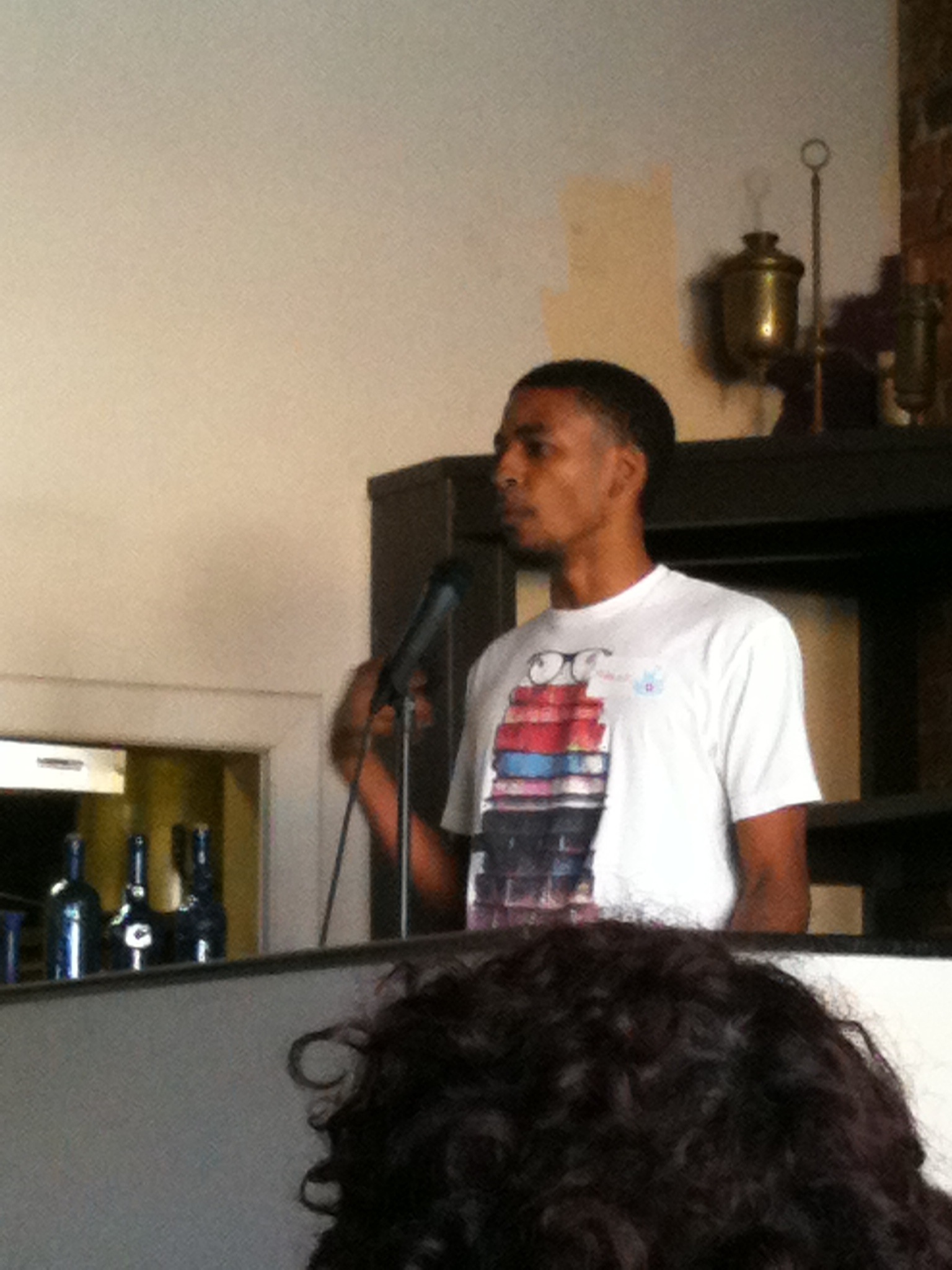

I could not help but observe, given recent discussions about diversity, that the attendees were pretty much split evenly between men and women and were 99% Caucasian. Based on these demographics it would be tempting for me to make some conclusions, however, before speaking about racial diversity in the skeptical movement I should note that the one African-American attendee was also a speaker whose talk was probably my highlight of the event.

---Marcus A. Davis is a young, enthusiastic speaker with a love for debunking conspiracy theories (especially if they involve lizard people). If his formula is anything to follow, inserting humor into debunking is a great idea.

While I was there I wondered, apart from being a skeptic and going to an event labeled as such, why do people come to events like these? One attendee told me “It’s good to be around like-minded people and to see what new ideas are out there.” Another told me that they enjoy the “exchange of ideas.” Still another attendee told me that she likes to “see what the kids are up to.” When I asked one of the event organizers, Jeff Wagg, why he thought events like these are important for the skeptical community, he told me that “[The event] gives people a direct connection to the skeptical community and access to answers that experts have or questions that they want to learn more about.”

Unfortunately, one of the drawbacks of small events like these is that you don’t get the same level of professionalism in talks that you would expect to see at a major conference like TAM. However, I don’t view this as a bad thing. Seeing regular people voice their opinions about different topics and watching scientists overcome a palpable unfamiliarity with a microphone was more endearing than jarring. There weren’t any talks that rivaled Sam Harris’, to be sure, but observing passionate skeptics eagerly sharing their ideas and answering questions as part of a community is far more important, in my view, than seeing someone who charges a speaker’s fee.

That being said, there were a number of interesting speakers who adeptly held listener attention, brining some polished aspect of science to the audience. One in particular was “The Skeptical Teacher” and veteran skeptic Matt Lowry. He adapted his talk from a lecture that he gives to his high school physics students about the reasoning behind the existence of Santa Claus (using mythology to instill critical thinking skills). In this talk he breathlessly and animatedly explained a number of calculations to demonstrate that Santa Claus would vaporize himself at the speeds necessary to reach all of the kids on Christmas, among other improbabilities.

I also learned some new things from Skepticamp Chicago. I learned that homeopathy is even more bogus than I previously thought, with the comparison of an “80X” dilution to one drop in the volume in the universe, I learned that FDA approval sometimes only signifies that the product is indeed a product, and I learned the four most common biases about evolution (progress, determinism, gradualism, and adaptationalism according to graduate student Nik Schuetz).

---Ali Marie, a well-spoken 19-year old skeptic and writer for Teen Skepchick, had a lot of good ideas on how to get teenagers more interested in science (one obvious suggestion was to move skeptical events out of the bars so that a younger audience, however exited, could actually attend the events).

One thing that I learned, arguably the most important thing, was not from any talk or discussion at the skepticamp, but from considering the event as a whole. Among a wide age range, in an overwhelmingly friendly atmosphere, being a skeptic now means not only being a critical thinker. Being a skeptic, as defined by events like these, also means being scientifically literate, well versed in statistics, well read, open to new ideas, friendly, and constantly informed. Seeing people come together in celebration of these values is heartening and encouraging for the future of skepticism.

If you can find a skepticamp in your area, I would readily recommend checking it out. It is a fun way to get involved in grassroots skepticism. You can learn something new, connect with friends (and make new ones), participate in interesting discussions and talks, and you can even give a talk yourself. While the public face of skepticism may be the major organizations, blogs, or public figures, skepticamps represent the people who make it all possible: enthusiastic skeptics who want to make an difference.

Kyle Hill is the newly appointed JREF research fellow specializing in communication research and human information processing. He writes daily at the Science-Based Life blog and you can follow him on Twitter here.